Learn about the dunder method __init__, responsible for initialising class instances.

Introduction

The dunder method __init__ is probably the first dunder method that Python programmers learn about.

When you first start defining your own classes, you are taught that you need to initialise your objects inside this crazy magic method called __init__,

and you don't really understand why that method has such a weird name.

When I first learned about __init__, I thought it was this magical method that worked in an obscure way...

But that is not true!

In what follows, I will try to demystify what __init__ does and how it works.

You can now get your free ✨ copy of the ebook “Pydon'ts – Write elegant Python code” on Gumroad to help support my Python 🐍 content.

What is __init__ for?

The dunder method __init__ is the method of your class that is responsible for initialising your object upon creation.

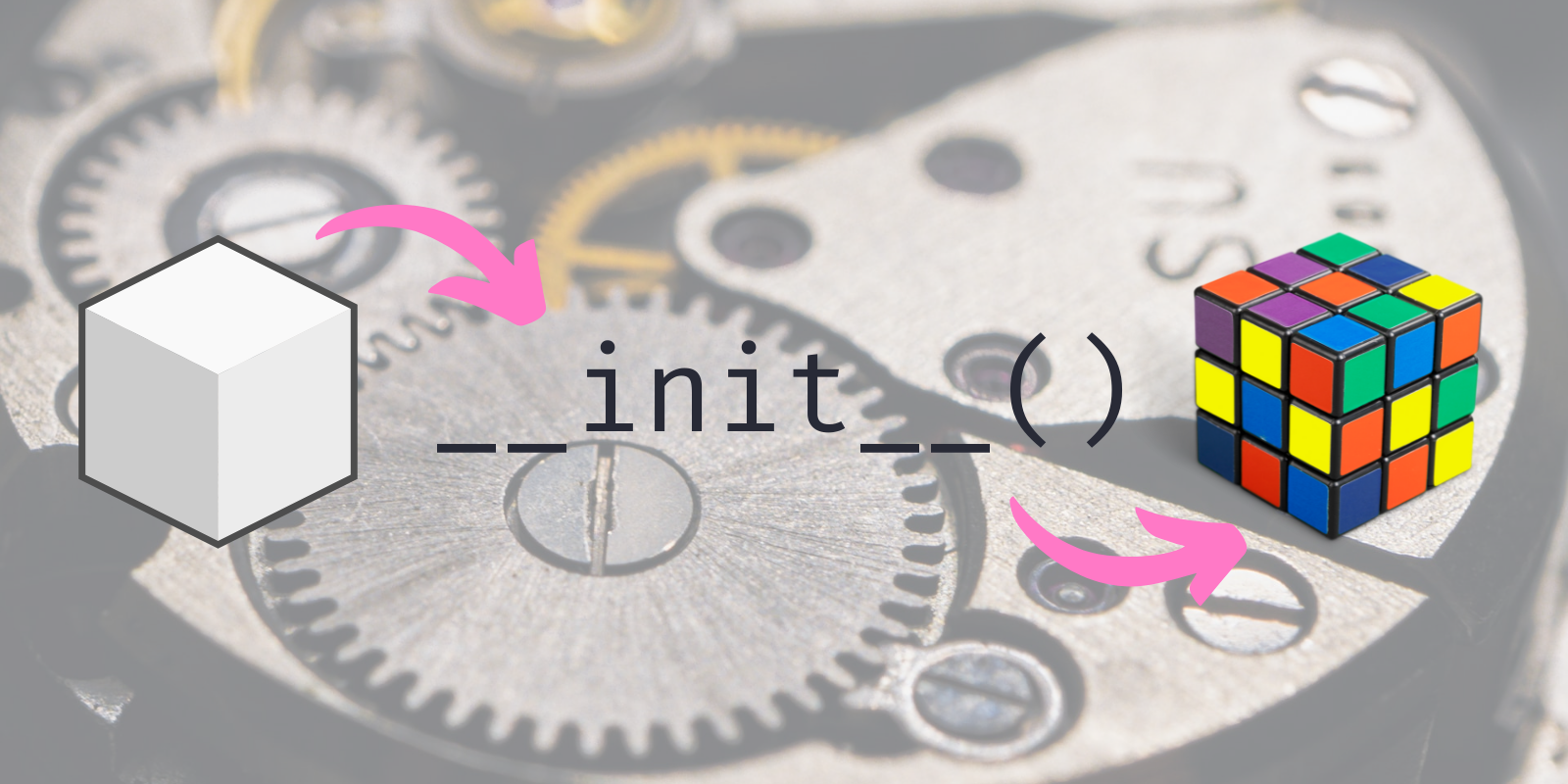

Just like the diagram above hints at, your method __init__ receives a fresh new instance of your class,

and it is at that point that you are free to customise it and adapt it,

according to the arguments that were passed in when the first instance was created.

For example, suppose you are a freelancer and you want to create a simple system to keep track of all your clients.

Maybe you would create a class Client,

and each client would have some information associated with them,

say, their name and their email.

Thus, to create a new instance of Client, you would need to pass in the name and email:

class Client:

# ...

# Create two clients:

alice = Client("Alice", "alice@example.com")

bob = Client("Bob", "bob@example.com")The rationale is that both the name and the email of the client stay associated with that object, and you associate those things to the objects when you initialise them.

Let us take a closer look at the line that creates the client Alice:

alice = Client("Alice", "alice@example.com")Notice that __init__ does not show up in that line.

And yet, when that line runs, the dunder method __init__ will be called...

And it will be given three pieces of information!

Obviously, the dunder method __init__ will receive the string name and the string email,

but there is one extra piece of information that __init__ will receive and that will actually come first.

self

The extra piece of information that __init__ receives is the object that __init__ is actually initialising!

Recall that __init__ is supposed to initialise your object upon creation,

so Python will create a blank Client object,

and then it will give it to you.

The dunder method __init__ accepts that blank Client object,

and that is what makes it possible for you to attach the name and email strings

as attributes of that instance.

The diagram below depicts this:

the blank cube goes into __init__, just like the string name and the string email.

It is the dunder method __init__ that actually puts the three together.

Notice that I called the blank Person argument self, and that is just a [Python naming convention][naming-matters#self].

(It is a deeply ingrained convention,

so you will definitely shock everyone around you if you change that name,

but it is just a name like any other.

You can change it to whatever you would like!)

What is interesting and “magical” is that we do not have to worry about passing that blank cube/blank instance of Person to the dunder method __init__ as the argument self,

it is Python that handles that on the backstage!

Taking all this into account,

the implementation of Client could look something like this:

class Client:

def __init__(self, name, email):

print(f"Creating the client {name} with email {email}.")

self.name = name

self.email = email

# Create two clients:

alice = Client("Alice", "alice@example.com")

# Creating the client Alice with email alice@example.com.

bob = Client("Bob", "bob@example.com")

# Creating the client Bob with email bob@example.com.Notice that the prints inside __init__ were triggered but we did not call the method __init__ explicitly.

The dunder method __init__ was called implicitly as part of the process of creating and customising each of the Client instances.

As in the example above, it is very common for the dunder method __init__ to save some/all of the arguments as attributes of the instance.

This makes that information available for later, so that the program/other methods can access it.

In fact, let us extend our class Client so that we can send emails to clients:

class Client:

def __init__(self, name, email):

print(f"Creating the client {name} with email {email}.")

self.name = name

self.email = email

def send_email(self, email_body):

print(f"To: {self.name} <{self.email}>")

print(email_body)

alice = Client("Alice", "alice@example.com")

# Creating the client Alice with email alice@example.com

alice.send_email("We need to schedule a meeting!")

# To: Alice <alice@example.com>

# We need to schedule a meeting!Introductory __init__ exercises

Here are a few exercises to help you come to grips with __init__.

- Implement a class

Personthat accepts a string argumentnameand saves it as an attribute.- Add a method

greetthat prints a greeting with that person's name.

- Add a method

- Implement a class

FullNamePersonthat accepts string argumentsfirst_nameandlast_nameand saves them in a single attributefull_name.- Add two methods to that class, one to retrieve the first name from the full name and another one to retrieve the last name from the full name.

- Implement a class

Point2Dthat accepts two numeric argumentsxandybut then saves them in a single tuple attribute. - Create an instance of

Point2Dwith arguments0and0and call itpoint.- Print the tuple attribute with the two zeroes.

- Try calling the method

__init__onpointdirectly, as if it were any other method; this time, pass in other arguments. - Print the tuple attribute again. What do you see?

- Go ahead and modify

Person.__init__so that the first argument is notself, then verify your code still works.

If some of the exercises are not clear, be sure to let me know, so that I can improve the wording!

__init__ and inheritance

Sometimes, our classes inherit from other classes, which means we get to reuse some of the behaviour they already define. When we inherit from another class, we have to be careful when initialising the subclass instance: we need to make sure that the parent class(es) get to do their initialisation! If that doesn't happen, things will be missing!

Let's go back to our Client class, which could be a subclass of Person.

If we assume all our clients are humans, that makes total sense.

Here is that relationship in code:

class Person:

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

class Client(Person):

def __init__(self, name, email):

self.name = name

self.email = email

def send_email(self, email_body):

print(f"To: {self.name} <{self.email}>")

print(email_body)Now, the issue is that there is duplication in the two dunder methods __init__:

in Person.__init__ and in Client.__init__.

To be honest, it isn't much: it's just the assignment to self.name...

But duplication is something to avoid.

What is more, we could easily extend the initialisation of the class Person,

and then Client would have to keep up...

And if we subclass Person or Client even further,

that is just going to become even messier.

To fix this, the subclass must call explicitly the dunder method __init__ of the parent class,

and that is done with the help of the built-in super,

which exists precisely to help us reach out to methods from parent classes!

By using super, here is how we would fix the implementation of Client.__init__:

class Person:

# ...

class Client(Person):

def __init__(self, name, email):

super().__init__(name)

self.email = email

# ...How does this work?

Think of it this way:

super() gives us access to the methods (dunder, or not) of the parent class,

so, after calling super(), it's as if we were looking at the “person” side of the client we are initialising.

Then, we call its __init__ method to do the initialisation that instances of Person need.

To do that, we need to provide the arguments that Person expects, which is just the name.

It is only after doing the parent class initialisation that we should do our own initialisation,

and that is why we only save the attribute self.email after calling super().__init__.

This order can be quite important, so, as a rule of thumb, it is always a good idea to start by initialising the parent class,

and only then the subclass.

In the exercises that follow, you will find a situation where ordering matters.

__init__ and inheritance exercises

- Create a class

Pointthat is the parent class ofPoint2D:-

Pointaccepts a single argument: an iterable (a list or a tuple, for example) with numbers and saves it in a tuple attribute. -

Point2Dstill accepts two arguments, but its initialisation is now done completely through the parent class__init__.

-

- Modify the class

Clientto accept a third argument,nice, which is a Boolean that says if the client is nice or not.- Create two subclasses of

Client,NiceClientandObnoxiousClient, that only need the argumentsnameandemail. When calling the parent class__init__, you should fill in the Boolean argumentniceyourself.

- Create two subclasses of

This exercise shows that creating subclasses doesn't necessarily mean that you are adding arguments. Sometimes, you remove arguments because some of them become implied.

- Modify the dunder method

__init__onPerson,Client, andNiceClient/ObnoxiousClientto include a call to the functionprintthat just says you are inside the respective__init__, then create an instance ofNiceClient/ObnoxiousClient. What do you see?

If you liked this article, be sure to leave a reaction below and share this with your friends and fellow Pythonistas. Also, don't forget to subscribe to the newsletter so you don't miss out on Python knowledge!

Become a better Python 🐍 developer 🚀

+35 chapters. +400 pages. Hundreds of examples. Over 30,000 readers!

My book “Pydon'ts” teaches you how to write elegant, expressive, and Pythonic code, to help you become a better developer. >>> Download it here 🐍🚀.

References

- Python 3 Documentation, Data model, https://docs.python.org/3/reference/datamodel.html [last accessed 10-07-2022];