This Pydon't will teach you how to use Python's conditional expressions.

(If you are new here and have no idea what a Pydon't is, you may want to read the Pydon't Manifesto.)

Introduction

Conditional expressions are what Python has closest to what is called a “ternary operator” in other languages.

In this Pydon't, you will:

- learn about the syntax of conditional expressions;

- understand the rationale behind conditional expressions;

- learn about the precedence of conditional expressions;

- see how to nest conditional expressions;

- understand the relationship between

if: ... elif: ... else:statements and conditional expressions; - see good and bad example usages of conditional expressions;

You can now get your free copy of the ebook “Pydon'ts – Write elegant Python code” on Gumroad to help support the series of “Pydon't” articles 💪.

What is a conditional expression?

A conditional expression in Python is an expression (in other words, a piece of code that evaluates to a result) whose value depends on a condition.

Expressions and statements

To make it clearer, here is an example of a Python expression:

>>> 3 + 4 * 5

23The code 3 + 4 * 5 is an expression, and that expression evaluates to 23.

Some pieces of code are not expressions.

For example, pass is not an expression because it does not evaluate to a result.

pass is just a statement, it does not “have” or “evaluate to” any result.

This might be odd (or not!) but to help you figure out if something is an expression or not,

try sticking it inside a print function.

Expressions can be used inside other expressions, and function calls are expressions.

Therefore, if it can go inside a print call, it is an expression:

>>> print(3 + 4 * 5)

23

>>> print(pass)

File "<stdin>", line 1

print(pass)

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntaxThe syntactic error here is that the statement pass cannot go inside the print function,

because the print function wants to print something,

and pass gives nothing.

Conditions

We are very used to using if statements to run pieces of code when certain conditions are met.

Rewording that, a condition can dictate what piece(s) of code run.

In conditional expressions, we will use a condition to change the value to which the expression evaluates.

Wait, isn't this the same as an if statement?

No!

Statements and expressions are not the same thing.

Syntax

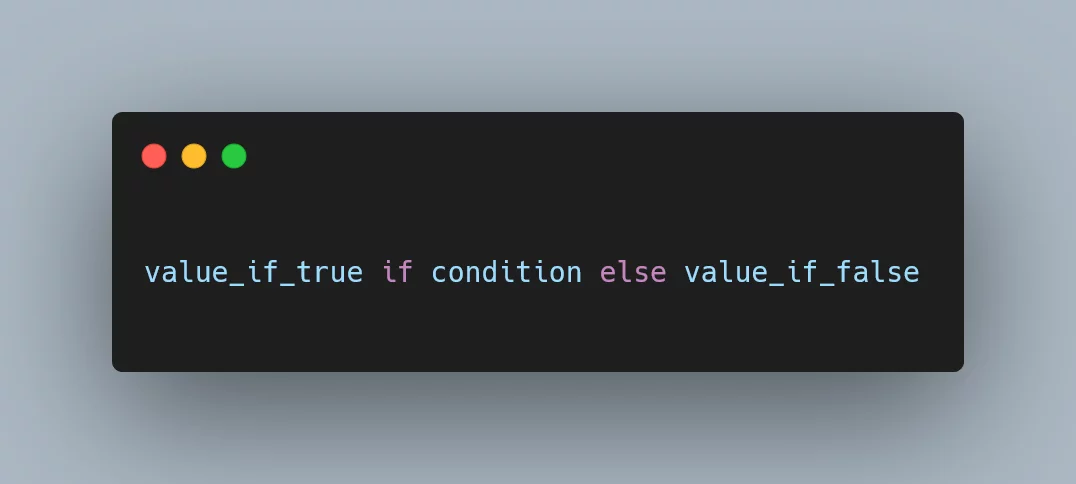

Instead of beating around the bush, let me just show you the anatomy of a conditional expression:

expr_if_true if condition else expr_if_falseA conditional expression is composed of three sub-expressions and the keywords if and else.

None of these components are optional.

All of them have to be present.

How does this work?

First, condition is evaluated.

Then, depending on whether condition evaluates to Truthy or Falsy,

the expression evaluates expr_if_true or expr_if_false, respectively.

As you may be guessing from the names,

expr_if_true and expr_if_false can themselves be expressions.

This means they can be simple literal values like 42 or "spam",

or other “complicated” expressions.

(Heck, the expressions in conditional expressions can even be other conditional expressions! Keep reading for that 😉)

Examples of conditional expressions

Here are a couple of simple examples,

broken down according to the expr_if_true, condition, and expr_if_false

anatomy presented above.

1.

>>> 42 if True else 0

42expr_if_true |

condition |

expr_if_false |

|---|---|---|

42 |

True |

0 |

2.

>>> 42 if False else 0

0expr_if_true |

condition |

expr_if_false |

|---|---|---|

42 |

False |

0 |

3.

>>> "Mathspp".lower() if pow(3, 27, 10) > 5 else "Oh boy."

'mathspp'expr_if_true |

condition |

expr_if_false |

|---|---|---|

"Mathspp".lower() |

pow(3, 27, 10) > 5 |

"Oh boy." |

For reference:

>>> pow(3, 27, 10)

7Reading a conditional expression

While the conditional expression presents the operands in an order that may throw some of you off, it is easy to read it as an English sentence.

Take this reference conditional expression:

value if condition else other_valueHere are two possible English “translations” of the conditional expression:

“Evaluate to

valueifconditionis true, otherwise evaluate toother_value.”

or

“Give

valueifconditionis true andother_valueotherwise.”

With this out of the way, ...

Does Python have a ternary operator?

Many languages have a ternary operator that looks like condition ? expr_if_true : expr_if_false.

Python does not have such a ternary operator, but conditional expressions are similar.

Conditional expressions are similar in that they evaluate one of two values,

but they are syntactically different because they use keywords (instead of ? and :)

and because the order of the operands is different.

Rationale

The rationale behind conditional expressions is simple to understand: programmers are often faced with a situation where they have to pick one of two values.

That's just it.

Whenever you find yourself having to choose between one value or another,

typically inside an if: ... else: ... block,

that might be a good use-case for a conditional expression.

Examples with if statements

Here are some simple functions that show that:

- computing the parity of an integer:

def parity(n):

if n % 2:

return "odd"

else:

return "even"

>>> parity(15)

"odd"

>>> parity(42)

"even"- computing the absolute value of a number (this already exists as a built-in function):

def abs(x):

if x > 0:

return x

else:

return -x

>>> abs(10)

10

>>> abs(-42)

42These two functions have a structure that is very similar:

they check a condition and return a given value if the condition

evaluates to True.

If it doesn't, they return a different value.

Refactored examples

Can you refactor the functions above to use conditional expressions? Here is one possible refactoring for each:

def parity(n):

return "odd" if n % 2 else "even"This function now reads as

“return

"odd"ifnleaves remainder when divided by2and"even"otherwise.”

As for the absolute value function,

def abs(n):

return x if x > 0 else -xit now reads as

“return

xifxis positive, otherwise return-x.”

Short-circuiting

You may be familiar with Boolean short-circuiting, in which case you might be pleased to know that conditional expressions also short-circuit.

For those of you who don't know Boolean short-circuiting yet, I can recommend my thorough Pydon't article on the subject. Either way, it's something to understand for our conditional expressions: a conditional expression will only evaluate what it really has to.

In other words, if your conditional expression looks like

expr_if_true if condition else expr_if_falsethen only one of expr_if_true and expr_if_false is ever evaluated.

This might look silly to point out, but is actually quite important.

Some times, we might want to do something (expr_if_true)

that only works if a certain condition is met.

For example, say we want to implement the quad-UCS function from APL.

That function is simple to explain:

it converts integers into characters and characters into integers.

In Python-speak, it just uses chr and ord,

whatever makes sense on the input.

Here is an example implementation:

def ucs(x):

if isinstance(x, int):

return chr(x)

else:

return ord(x)

>>> ucs("A")

65

>>> ucs(65)

'A

>>> ucs(102)

'f'

>>> ucs("f")

102What isn't clear from this piece of code is that

ord throws an error when called on integers,

and chr fails when called on characters:

>>> ord(65)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: ord() expected string of length 1, but int found

>>> chr("f")

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: an integer is required (got type str)Thankfully, this is not a problem for conditional expressions,

and therefore ucs can be implemented with one:

def ucs(x):

return chr(x) if isinstance(x, int) else ord(x)

>>> ucs("A")

65

>>> ucs(65)

'A

>>> ucs(102)

'f'

>>> ucs("f")

102Therefore, we see that when x is an integer, ord(x) never runs.

On the flip side, when x is not an integer, chr(x) never runs.

This is a very useful subtlety!

Conditional expressions and if statements

Equivalence to if

This has been implicit throughout the article, but I'll write it down explicitly now for the sake of clarity.

(And also because “Explicit is better than implicit.” 😁!)

There is a close relationship between the conditional expression

name = expr_if_true if condition else expr_if_falseand the if statement

if condition:

name = expr_if_true

else:

name = expr_if_falseAnd that close relationship is that of equivalence. The two pieces of code are exactly equivalent.

Equivalence to if-elif-else blocks

Given the equivalence between conditional expressions and if: ... else: ... blocks,

it is natural to wonder whether there is some equivalent to the elif statement

in conditional expressions as well.

For example, can we rewrite the following function to use a conditional expression?

def sign(x):

if x == 0:

return 0

elif x > 0:

return 1

else:

return -1

>>> sign(-73)

-1

>>> sign(0)

0

>>> sign(42)

1How can we write this as a conditional expression?

Conditional expressions do not allow the usage of the elif keyword so,

instead, we start by reworking the if block itself:

def sign(x):

if x == 0:

return 0

else:

if x > 0:

return 1

else:

return -1This isn't a great implementation,

but this intermediate representation makes it clearer that the bottom

of the if block can be replaced with a conditional expression:

def sign(x):

if x == 0:

return 0

else:

return 1 if x > 0 else -1Now, if we abstract away from the fact that the second return value

is a conditional expression itself,

we can rewrite the existing if block as a conditional expression:

def sign(x):

return 0 if x == 0 else (1 if x > 0 else -1)

>>> sign(-73)

-1

>>> sign(0)

0

>>> sign(42)

1This shows that conditional expressions can be nested, naturally. Now it is just a matter of checking whether the parentheses are needed or not.

In other words, if we write

A if B else C if D else Edoes Python interpret it as

(A if B else C) if D else Eor does it interpret it as

A if B else (C if D else E)As it turns out, it's the latter.

So, the sign function above can be rewritten as

def sign(x):

return 0 if x == 0 else 1 if x > 0 else -1It's this chain of if ... else ... if ... else ... –

that can be arbitrarily long – that emulates elifs.

To convert from a long if block (with or without elifs)

to a conditional expression,

go from top to bottom and interleave values and conditions,

alternating between the keyword if and the keyword else.

When reading this aloud in English, the word “otherwise” helps clarify what the longer conditional expressions mean:

return 0 if x == 0 else 1 if x > 0 else -1reads as

“return 0 if x is 0, otherwise, return 1 if x is positive otherwise return -1.”

The repetition of the word “otherwise” becomes cumbersome, a good indicator that it is generally not a good idea to get carried away and chaining several conditional expressions.

For reference, here's a “side-by-side” comparison of the first conditional block and the final conditional expression:

# Compare

if x == 0:

return 0

elif x > 0:

return 1

else:

return -1

# to:

return 0 if x == 0 else 1 if x > 0 else -1Non-equivalence to function wrapper

Because of the equivalence I just showed,

many people may then believe that conditional expressions

could be implemented as a function enclosing the previous if: ... else: ... block:

def cond(condition, value_if_true, value_if_false):

if condition:

return value_if_true

else:

return value_if_falseWith this definition, we might think we have implemented conditional expressions:

>>> cond(pow(3, 27, 10) > 5, "Mathspp".lower(), "Oh boy.")

'mathspp'

>>> "Mathspp".lower() if pow(3, 27, 10) > 5 else "Oh boy."

'mathspp'In fact, we haven't!

That's because the function call to cond only happens

after we have evaluated all the arguments.

This is different from what conditional expressions really do:

as I showed above,

conditional expressions only evaluate the expression they need.

Hence, we can't use this cond to implement ucs:

def ucs(x):

return cond(isinstance(x, int), chr(x), ord(x))This code looks sane, but it won't behave like we would like:

>>> ucs(65)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "<stdin>", line 2, in ucs

TypeError: ord() expected string of length 1, but int foundWhen given 65, the first argument evaluates to True,

and the second argument evaluates to "A",

but the third argument raises an error!

Precedence

Conditional expressions are the expressions with lowest precedence, according to the documentation.

This means that sometimes you may need to parenthesise a conditional expression if you are using it inside another expression.

For example, take a look at this function:

def foo(n, b):

if b:

to_add = 10

else:

to_add = -10

return n + to_add

>>> foo(42, True)

52

>>> foo(42, False)

32You might spot the pattern of assigning one of two values, and decide to use a conditional expression:

def foo(n, b):

to_add = 10 if b else -10

return n + to_add

>>> foo(42, True)

52

>>> foo(42, False)

32But then, you decide there is no need to waste a line here,

and you decide to inline the conditional expression

(that is, you put the conditional expression inside

the arithmetic expression with n +):

def foo(n, b):

return n + 10 if b else -10By doing this, you suddenly break the function when b is False:

>>> foo(42, False)

-10That's because the expression

n + 10 if b else -10is seen by Python as

(n + 10) if b else -10while you meant for it to mean

n + (10 if b else -10)In other words, and in not-so-rigourous terms,

the + “pulled” the neighbouring 10 and it's the whole

n + 10 that is seen as the expression to evaluate if the condition

evaluates to Truthy.

Conditional expressions that evaluate to Booleans

Before showing good usage examples of conditional expressions, let me just go ahead and show you something you should avoid when using conditional expressions

Conditional expressions are suboptimal when they evaluate to Boolean values.

Here is a silly example:

def is_huge(n):

return True if n > pow(10, 10) else FalseCan you see what is wrong with this implementation of is_huge?

This function might look really good, because it is short and readable, and its behaviour is clear:

>>> is_huge(3.1415)

False

>>> is_huge(999)

False

>>> is_huge(73_324_634_325_242)

TrueHowever... The conditional expression isn't doing anything relevant! The conditional expression just evaluates to the same value as the condition itself!

Take a close look at the function.

If n > pow(10, 10) evaluates to True, then we return True.

If n > pow(10, 10) evaluates to False, then we return False.

Here is a short table summarising this information:

n > pow(10, 10) evaluates to... |

We return... |

|---|---|

True |

True |

False |

False |

So, if the value of n > pow(10, 10) is the same as the thing we return,

why don't we just return n > pow(10, 10)?

In fact, that's what we should do:

def is_huge(n):

return n > pow(10, 10)Take this with you:

never use if: ... else: ... or conditional expressions to evaluate to/return Boolean values.

Often, it suffices to work with the condition alone.

A related use case where conditional expressions shouldn't be used

is when assigning default values to variables.

Some of these default values can be assigned with Boolean short-circuiting, using the or operator.

Examples in code

Here are a couple of examples where conditional expressions shine.

You will notice that these examples aren't particularly complicated or require much context to understand the mechanics of what is happening.

That's because the rationale behind conditional expressions is simple: pick between two values.

The dictionary .get method

The

collections

has a ChainMap class.

This can be used to chain several dictionaries together, as I've shown in a tweet in the past:

In #Python, you can use `collections.ChainMap` to create a larger mapping out of several other maps. Useful, for example, when you want to juxtapose user configurations with default configurations.

— Rodrigo 🐍📝 (@mathsppblog) June 4, 2021

Follow for more #tips about Python 🐍#learnpython #learncode #100daysofcode pic.twitter.com/ip9IInItYG

What's interesting is that ChainMap also defines a .get method,

much like a dictionary.

The .get method tries to retrieve a key and returns a default value if it finds it:

>>> from collections import ChainMap

>>> user_config = {"name": "mathspp"}

>>> default_config = {"name": "<noname>", "fullscreen": True}

# Access a key directly:

>>> config["fullscreen"]

True

# config["darkmode"] would've failed with a KeyError.

>>> config.get("darkmode", False)

FalseHere is the full implementation of the .get method:

# From Lib/collections/__init__.py in Python 3.9.2

class ChainMap(_collections_abc.MutableMapping):

# ...

def get(self, key, default=None):

return self[key] if key in self else defaultSimple!

Return the value associated with the key if key is in the dictionary,

otherwise return the default value!

Just that.

Resolving paths

The module pathlib is great when you need to deal with paths.

One of the functionalities provided is the .resolve method,

that takes a path and makes it absolute,

getting rid of symlinks along the way:

# Running this from C:/Users/rodri:

>>> Path("..").resolve()

WindowsPath('C:/Users')

# The current working directory is irrelevant here:

>>> Path("C:/Users").resolve()

WindowsPath('C:/Users')Here is part of the code that resolves paths:

# In Lib/pathlib.py from Python 3.9.2

class _PosixFlavour(_Flavour):

# ...

def resolve(self, path, strict=False):

# ...

base = '' if path.is_absolute() else os.getcwd()

return _resolve(base, str(path)) or sepAs you can see, before calling the auxiliary function _resolve and returning,

the function figures out if there is a need to add a base to the path.

If the path I enter is relative, like the ".." path above,

then the base is set to be the current working directory (os.getcwd()).

If the path is absolute, then there is no need for a base,

because it is already there.

Conclusion

Here's the main takeaway of this Pydon't, for you, on a silver platter:

“Conditional expressions excel at evaluating to one of two distinct values, depending on the value of a condition.”

This Pydon't showed you that:

- conditional expressions are composed of three sub-expressions interleaved with the

ifandelsekeywords; - conditional expressions were created with the intent of providing a convenient way of choosing between two values depending on a condition;

- conditional expressions can be easily read out as English statements;

- conditional expressions have the lowest precedence of all Python expressions;

- short-circuiting ensures conditional expressions only evaluate one of the two “value expressions”;

- conditional expressions can be chained together to emulate

if: ... elif: ... else: ...blocks; - it is impossible to emulate a conditional expression with a function; and

- if your conditional expression evaluates to a Boolean, then you should only be working with the condition.

If you liked this Pydon't be sure to leave a reaction below and share this with your friends and fellow Pythonistas. Also, subscribe to the newsletter so you don't miss a single Pydon't!

Become a better Python 🐍 developer 🚀

+35 chapters. +400 pages. Hundreds of examples. Over 30,000 readers!

My book “Pydon'ts” teaches you how to write elegant, expressive, and Pythonic code, to help you become a better developer. >>> Download it here 🐍🚀.

References

- Python 3 Docs, The Python Language Reference, Conditional Expressions, https://docs.python.org/3/reference/expressions.html#conditional-expressions [last accessed 28-09-2021];

- PEP 308 -- Conditional Expressions, https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0308/ [last accessed 28-09-2021];

- Python 3 Docs, The Python Standard Library,

collections.ChainMap, https://docs.python.org/3/library/collections.html#chainmap-objects [last accessed 28-09-2021]; - Python 3 Docs, The Python Standard Library,

pathlib.Path.resolve, https://docs.python.org/3/library/pathlib.html#pathlib.Path.resolve [last accessed 28-09-2021]; - “Does Python have a ternary conditional operator?”, Stack Overflow question and answers, https://stackoverflow.com/questions/394809/does-python-have-a-ternary-conditional-operator [last accessed 28-09-2021];

- “Conditional Expressions in Python”, note.nkmk.me, https://note.nkmk.me/en/python-if-conditional-expressions/ [last accessed 28-09-2021];

- “Conditional Statements in Python, Conditional Expressions (Python's Ternary Operator)”, Real Python, https://realpython.com/python-conditional-statements/#conditional-expressions-pythons-ternary-operator [last accessed 28-09-2021];