This is the third article of the “Building a Python compiler and interpreter” series, so make sure you've gone through the first two articles before tackling this one!

The code that serves as a starting point for this article is the tag v0.2.0 of the code in this GitHub repository.

Objectives

The objectives for this article are the following:

- understand what a language grammar is and how it will shape the design of the parser;

- learn about the visitor pattern and see how much flexible it makes our compiler and interpreter; and

- add support for consecutive additions and subtractions.

Language grammar

A language grammar is a way of representing the syntax that is valid in a given language. The exact notation varies a bit but the gist is always the same. In a language grammar you write "rules" that represent what is valid in your language and each rule has two parts:

- the name of the rule; and

- the "body" of the rule, which represents the syntax that matches the rule.

Naturally, rules can reference each other and that is what introduces freedom (but also complexity) to the grammars (and, ultimately, to our programming language).

The grammar of our language

Right now, the grammar that represents the subset of Python that we support could be represented as such:

program := computation EOF

computation := number (PLUS | MINUS) number

number := INT | FLOATWe write rules in lowercase and token types in upper case.

So, in the grammar above, the words program, computation, and number refer to grammar rules while the words EOF, PLUS, MINUS, INT, and FLOAT, refer to token types.

The rule program reads

program := computation EOFThis means that a program is a computation followed by an EOF token.

In turn, the rule computation reads

computation := number (PLUS | MINUS) numberThis means that a computation is a number, followed by a plus sign or a minus sign, and then another number.

Notice how we use the symbol | to represent alternatives, so PLUS | MINUS means "a plus or a minus".

Finally, the rule number reads

number := INT | FLOATThis rule means that a number is either an INT token or a FLOAT token.

Relationship between the grammar and the parser

Here is the full grammar, once again:

program := computation EOF

computation := number (PLUS | MINUS) number

number := INT | FLOATNow, here is the skeleton of our parser:

class Parser:

# ...

def parse_number(self) -> Int | Float:

"""Parses an integer or a float."""

...

def parse_computation(self) -> BinOp:

"""Parses a computation."""

...

def parse(self) -> BinOp:

"""Parses the program."""

...Notice how we have a parse method for each of the grammar rules and notice how there is a correspondence between each rule and the implementation of the parse method. Below you can find the three parse methods and the respective grammar rule in the docstring of the method.

Pay attention to what's written in each rule versus the implementation of the parse method.

Notice how the body of the grammar rule dictates what the implementation looks like.

If a rule is referenced in the body of the rule, we call its parse method.

If a token type is referenced in the body of the rule, we call the method eat to consume that token.

class Parser:

# ...

def parse_number(self) -> Int | Float:

"""Parses an integer or a float.

number := INT | FLOAT

"""

if self.peek() == TokenType.INT:

return Int(self.eat(TokenType.INT).value)

else:

return Float(self.eat(TokenType.FLOAT).value)

def parse_computation(self) -> BinOp:

"""Parses a computation.

computation := number (PLUS | MINUS) number

"""

left = self.parse_number()

if self.peek() == TokenType.PLUS:

op = "+"

self.eat(TokenType.PLUS)

else:

op = "-"

self.eat(TokenType.MINUS)

right = self.parse_number()

return BinOp(op, left, right)

def parse(self) -> BinOp:

"""Parses the program.

program := computation EOF

"""

computation = self.parse_computation()

self.eat(TokenType.EOF)

return computationThis should show you how helpful the language grammar is. Throughout this series, whenever we want to add support for anything to our language, we will modify the language grammar and that will help us understand how to modify the parser to accomodate for those changes.

We will see this soon enough, as we change our grammar to add support for successive additions and subtractions, unary operators and parenthesised expressions.

For now, we'll just write the full grammar as the docstring for the parser:

class Parser:

"""

program := computation

computation := number (PLUS | MINUS) number

number := INT | FLOAT

"""

# ...The grammar rules everything

You don't know it yet, because you haven't finished this article, but the grammar will rule everything. The parser mimics the grammar, and the compiler and interpreter will be built around the parser, so the grammar is the one thing that will influence everything else.

So, in a sense, knowing how to modify the grammar to add new features to the language will be the key thing to understand. The more we work with the grammar, the better you'll get at this. For now, I'll leave you with some thoughts.

We could've written the previous grammar as such:

program := computation EOF

computation := (INT | FLOAT) (PLUS | MINUS) (INT | FLOAT)But we didn't. We created a rule to parse the type of number. This would make it easier, for example, to add complex numbers, or fractions, or other types of numbers.

In general, we will try to keep our grammar rules as simple as possible and the hierarchy of the rules can have repercussions in the priority of operations. Thus, going forward, we'll want to keep this in mind.

For example, notice how the EOF is mentioned at the topmost rule (the rule program) and, at the same time, the token EOF is the last one to be eaten when parsing the tokens.

Conversely, the rule for number is "at the bottom" of the nesting of rules, and a number is the first thing we parse in our program.

So, rules that are "deep" within the grammar correspond to things that tend to be parsed "first", which means depth can be used to control priority of operations, for example.

This may be a bit abstract for now, but it'll become clearer by the end of this article and over the next few articles.

Consecutive additions and subtractions

We want to add support for consecutive additions and subtractions to our programming language. In other words, we want to be able to support programs like the following:

1 + 2 + 31 - 2 - 35 - 3 + 4 + 11 - 7

Grammar modifications

In order to do this, we need to change our grammar rule computation, because currently a computation is a single addition or subtraction.

So, our rule computation currently looks like this:

computation := number (PLUS | MINUS) numberWe will modify it so that it looks like this:

computation := number ( (PLUS | MINUS) number )*Notice how we added (...)* around the last part of the rule.

Similarly to regex, the symbol * is used to represent repetition; in particular, * next to something means that that thing may show up 0 or more times.

So, we went from "a computation is a number, followed by a plus or a minus, followed by a number" to "a computation is a number, followed by 0 or more repetitions of a plus or a minus sign followed by a number".

Nesting subtrees

In our parse method, this means that now we will use a while loop to parse as many repetitions of the part (PLUS | MINUS) number as possible.

Then, for each repetition, we will grow our AST:

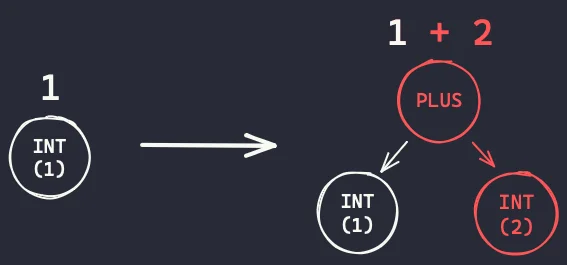

-

1is represented by the ASTone = Int(1) -

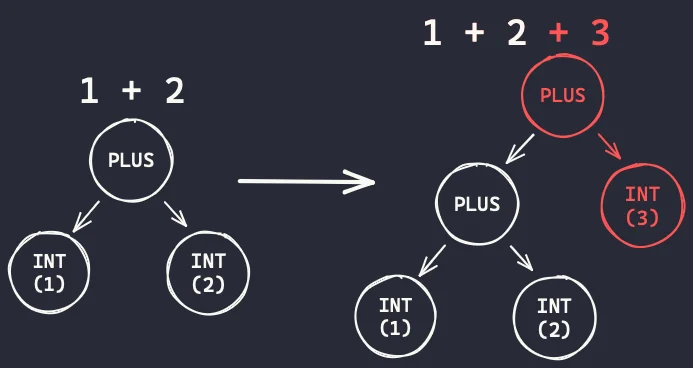

1 + 2is represented by the ASTthree = BinOp("+", one, Int(2)); -

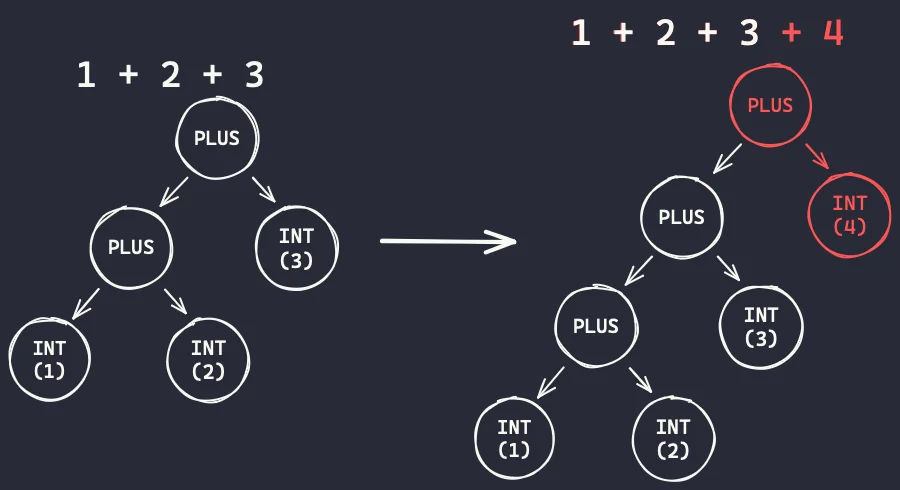

1 + 2 + 3is represented by the ASTsix = BinOp("+", three, Int(3)); and -

1 + 2 + 3 + 4is represented by the ASTBinOp("+", six, Int(4)).

Notice how the previous result becomes the left child of the next binary operation. The diagrams below represent this!

We start off by parsing the number 1, and when we identify that there is a plus sign coming, we parse the plus sign, the next number, and we put the 1 on the left:

After parsing 1 + 2, when we identify that there is a plus sign coming, we parse the plus sign, the next number, and we put the 1 + 2 on the left:

Finally, after parsing 1 + 2 + 3, when we identify that there is a plus sign coming, we parse the plus sign, the next number, and we put the 1 + 2 + 3 on the left:

We can modify the method parse_computation to implement the algorithm that we illustrated above:

class Parser:

# ...

def parse_computation(self) -> BinOp:

"""Parses a computation."""

result = self.parse_number()

while (next_token := self.peek()) in {TokenType.PLUS, TokenType.MINUS}:

op = "+" if next_token_type == TokenType.PLUS else "-"

self.eat(next_token_type)

right = self.parse_number()

result = BinOp(op, result, right)

return resultIn the code above we modified the body of the method parse_computation but now we have a small problem: we broke typing.

For example, BinOp expects an Int or a Float as its left child, but now we are building the tree up and we might end up putting another BinOp on the left.

To fix this, we'll rework our AST a bit.

An AST node for expressions

What we need is to recognise that integers, floats, and binary operations all have something in common: they are expressions.

They are pieces of code that produce a value that can be saved in a variable, printed, or used for something else.

So, we are going to create an AST node for expressions and then the nodes BinOp, Int, and Float will inherit from that node:

@dataclass

class TreeNode:

pass

@dataclass

class Expr(TreeNode): # <-- New node type!

pass

@dataclass

class BinOp(Expr): # <-- BinOp is an Expr.

op: str

left: Expr # <-- BinOp's children are

right: Expr # <-- also Expr.

@dataclass

class Int(Expr): # <-- Int is an Expr.

value: int

@dataclass

class Float(Expr): # <-- Float is an Expr.

value: floatAfter we create said Expr node, we can fix the annotations of the methods parse and parse_computation:

class Parser:

# ...

def parse_computation(self) -> Expr: # <-- Now we return an Expr...

"""Parses a computation."""

result: Expr # <-- ... so the result is an Expr.

result = self.parse_number()

while (next_token := self.peek()) in {TokenType.PLUS, TokenType.MINUS}:

op = "+" if next_token_type == TokenType.PLUS else "-"

self.eat(next_token_type)

right = self.parse_number()

result = BinOp(op, result, right)

return result

def parse(self) -> Expr: # <-- Now we return an Expr.

"""Parses the program."""

computation = self.parse_computation()

self.eat(TokenType.EOF)

return computationTesting the new parser

After these changes, we run pytest . to see if we broke something that was working.

As it turns out, it looks like we didn't break anything.

Now, we supposedly can parse an arbitrary number of additions and subtractions, so we can see this in action by using the parser and the function print_ast:

if __name__ == "__main__":

from .tokenizer import Tokenizer

code = "3 + 5 - 7"

parser = Parser(list(Tokenizer(code)))

print_ast(parser.parse())Running this code prints the following output:

-

+

3

5

7Remember that the operations that are at the top of the tree are the operations that happen later, so the tree above shows that the - happens after computing 3 + 5.

It's the result of 3 + 5 that is the left operand to the -, which will then subtract 7 from that value.

Now, we add a couple of tests to the parser. We start by making sure we can parse single numbers, as well as a couple of operations in a row:

def test_parsing_single_integer():

tokens = [

Token(TokenType.INT, 3),

Token(TokenType.EOF),

]

tree = Parser(tokens).parse()

assert tree == Int(3)

def test_parsing_single_float():

tokens = [

Token(TokenType.FLOAT, 3.0),

Token(TokenType.EOF),

]

tree = Parser(tokens).parse()

assert tree == Float(3.0)

def test_parsing_addition_then_subtraction():

tokens = [

Token(TokenType.INT, 3),

Token(TokenType.PLUS),

Token(TokenType.INT, 5),

Token(TokenType.MINUS),

Token(TokenType.FLOAT, 0.2),

Token(TokenType.EOF),

]

tree = Parser(tokens).parse()

assert tree == BinOp(

"-",

BinOp(

"+",

Int(3),

Int(5),

),

Float(0.2),

)

def test_parsing_subtraction_then_addition():

tokens = [

Token(TokenType.INT, 3),

Token(TokenType.MINUS),

Token(TokenType.INT, 5),

Token(TokenType.PLUS),

Token(TokenType.FLOAT, 0.2),

Token(TokenType.EOF),

]

tree = Parser(tokens).parse()

assert tree == BinOp(

"+",

BinOp(

"-",

Int(3),

Int(5),

),

Float(0.2),

)Modifying the function print_ast

Now, I want to add another test with multiple additions and subtractions, but it will be a pain to write that tree by hand, so I will actually modify the function print_ast to print the AST in a way that I can copy and paste:

def print_ast(tree: TreeNode, depth: int = 0) -> None:

indent = " " * depth

node_name = tree.__class__.__name__

match tree:

case BinOp(op, left, right):

print(f"{indent}{node_name}(\n{indent} {op!r},")

print_ast(left, depth + 1)

print(",")

print_ast(right, depth + 1)

print(f",\n{indent})", end="")

case Int(value) | Float(value):

print(f"{indent}{node_name}({value!r})", end="")

case _:

raise RuntimeError(f"Can't print a node of type {nome_name}")

if depth == 0:

print()Now, we can use this function to print the tree associated with the expression 3 + 5 - 7 + 1.2 + 2.4 - 3.6:

if __name__ == "__main__":

from .tokenizer import Tokenizer

code = "3 + 5 - 7 + 1.2 + 2.4 - 3.6"

parser = Parser(list(Tokenizer(code)))

print_ast(parser.parse())Running the code above creates the tree that I copied and pasted into the final test that I added to the parser:

def test_parsing_many_additions_and_subtractions():

# 3 + 5 - 7 + 1.2 + 2.4 - 3.6

tokens = [

Token(TokenType.INT, 3),

Token(TokenType.PLUS),

Token(TokenType.INT, 5),

Token(TokenType.MINUS),

Token(TokenType.INT, 7),

Token(TokenType.PLUS),

Token(TokenType.FLOAT, 1.2),

Token(TokenType.PLUS),

Token(TokenType.FLOAT, 2.4),

Token(TokenType.MINUS),

Token(TokenType.FLOAT, 3.6),

Token(TokenType.EOF),

]

tree = Parser(tokens).parse()

assert tree == BinOp(

"-",

BinOp(

"+",

BinOp(

"+",

BinOp(

"-",

BinOp(

"+",

Int(3),

Int(5),

),

Int(7),

),

Float(1.2),

),

Float(2.4),

),

Float(3.6),

)Compiling the new grammar

Now that we are capable of parsing more intricate ASTs, we need to modify our compiler to cope with these new features. As it stands, the compiler still expects to receive a tree of a single addition or subtraction.

The compiler has no idea how complex the tree it will compile is. So, we need to implement the compiler in such a way that makes it easy for us to modify in the future as we add more operations and features to the language. To do this, we will use the visitor pattern.

If you want, you can read more about the visitor pattern on Wikipedia, but I'll give you the gist of it.

The visitor pattern depends on a sort of dispatch method. This dispatch method will accept an arbitrary tree node, and its job is to use some dynamic inspection to figure out what is the type of the tree node. Then, it will dispatch the compilation of that tree node to the appropriate method.

Assume the dispatch method is called _compile.

The idea is that:

- if we call

_compile(BinOp(...)), then_compilewill callcompile_BinOp(BinOp(...)); - if we call

_compile(Int(...)), then_compilewill callcompile_Int(Int(...)); and - if we call

_compile(Float(...)), then_compilewill callcompile_Float(Float(...)).

The implementation of the method _compile can be seen below, together with a type statement to create a type alias that we'll be using a lot:

type BytecodeGenerator = Generator[Bytecode, None, None]

class Compiler:

# ...

def _compile(self, tree: TreeNode) -> BytecodeGenerator:

node_name = tree.__class__.__name__

compile_method = getattr(self, f"compile_{node_name}", None)

if compile_method is None:

raise RuntimeError(f"Can't compile {node_name}.")

yield from compile_method(tree)Now, we just need to implement each of the compile_XXX methods:

class Compiler:

# ...

def compile_BinOp(self, tree: BinOp) -> BytecodeGenerator:

yield from self._compile(tree.left)

yield from self._compile(tree.right)

yield Bytecode(BytecodeType.BINOP, tree.op)

def compile_Int(self, tree: Int) -> BytecodeGenerator:

yield Bytecode(BytecodeType.PUSH, tree.value)

def compile_Float(self, tree: Float) -> BytecodeGenerator:

yield Bytecode(BytecodeType.PUSH, tree.value)Notice how the method compile_BinOp calls _compile again!

After all, we don't know if the left and right children of a binary operation are other binary operations, integers, or floats!

Finally, we make sure that the entry point, the method compile, kicks things off:

class Compiler:

# We compile any tree vvvvvvvv

def __init__(self, tree: TreeNode) -> None:

self.tree = tree

def compile(self) -> BytecodeGenerator:

yield from self._compile(self.tree)Testing the compilation

We've refactored the compiler, so it's a good idea to make sure we didn't break it: pytest ..

We can also take the new compiler for a spin:

if __name__ == "__main__":

from .tokenizer import Tokenizer

from .parser import Parser

compiler = Compiler(Parser(list(Tokenizer("3 + 5 - 7 + 1.2 + 2.4 - 3.6"))).parse())

for bc in compiler.compile():

print(bc)Running the code above with python -m python.compiler produces the following output:

Bytecode(BytecodeType.PUSH, 3) # <-

Bytecode(BytecodeType.PUSH, 5) # <-

Bytecode(BytecodeType.BINOP, '+')

Bytecode(BytecodeType.PUSH, 7) # <-

Bytecode(BytecodeType.BINOP, '-')

Bytecode(BytecodeType.PUSH, 1.2) # <-

Bytecode(BytecodeType.BINOP, '+')

Bytecode(BytecodeType.PUSH, 2.4) # <-

Bytecode(BytecodeType.BINOP, '+')

Bytecode(BytecodeType.PUSH, 3.6) # <-

Bytecode(BytecodeType.BINOP, '-')Notice how the bytecodes start by pushing two numbers in a row, but then they alternate with an operation. This pattern will only be broken when we add support for parenthesised expressions, which will allow changing the order of operations.

We'll go to the big tree from the last test we added to the parser and we'll add it to the compiler now:

def test_compile_nested_additions_and_subtractions():

tree = BinOp(

"-",

BinOp(

"+",

BinOp(

"+",

BinOp(

"-",

BinOp(

"+",

Int(3),

Int(5),

),

Int(7),

),

Float(1.2),

),

Float(2.4),

),

Float(3.6),

)

bytecode = list(Compiler(tree).compile())

assert bytecode == [

Bytecode(BytecodeType.PUSH, 3),

Bytecode(BytecodeType.PUSH, 5),

Bytecode(BytecodeType.BINOP, "+"),

Bytecode(BytecodeType.PUSH, 7),

Bytecode(BytecodeType.BINOP, "-"),

Bytecode(BytecodeType.PUSH, 1.2),

Bytecode(BytecodeType.BINOP, "+"),

Bytecode(BytecodeType.PUSH, 2.4),

Bytecode(BytecodeType.BINOP, "+"),

Bytecode(BytecodeType.PUSH, 3.6),

Bytecode(BytecodeType.BINOP, "-"),

]Adding the visitor pattern to the interpreter as well

Given that the interpreter had been implemented as a loop already, the interpreter doesn't really need to be modified in order for it to work with multiple additions and subtractions.

In fact, running python -m python.interpreter "3 + 5 - 7 + 1.2 + 2.4 - 3.6" should give the "expected" result of

Done!

Stack([1.0000000000000004])However, it turns out that the visitor pattern is also an excellent idea for the interpreter and it will make it much easier to extend the interpreter for the next additions to the language. Hence, we'll implement the visitor pattern on the bytecode types as well:

class Interpreter:

# ...

def interpret(self) -> None:

for bc in self.bytecode:

bc_name = bc.type.value

interpret_method = getattr(self, f"interpret_{bc_name}", None)

if interpret_method is None:

raise RuntimeError(f"Can't interpret {bc_name}.")

interpret_method(bc)

print("Done!")

print(self.stack)

def interpret_push(self, bc: Bytecode) -> None:

self.stack.push(bc.value)

def interpret_binop(self, bc: Bytecode) -> None:

right = self.stack.pop()

left = self.stack.pop()

if bc.value == "+":

result = left + right

elif bc.value == "-":

result = left - right

else:

raise RuntimeError(f"Unknown operator {bc.value}.")

self.stack.push(result)Testing the interpreter

Now that we've gone through the whole program, we can add some tests for these new changes to the interpreter in test_interpreter.py:

@pytest.mark.parametrize(

["code", "result"],

[

("1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5", 15),

("1 - 2 - 3", -4),

("1 - 2 + 3 - 4 + 5 - 6", -3),

],

)

def test_sequences_of_additions_and_subtractions(code: str, result: int):

assert run_computation(code) == resultYou may notice the function run_computation that I added in the test.

It's just a helper function that I defined now:

def run_computation(code: str) -> int:

tokens = list(Tokenizer(code))

tree = Parser(tokens).parse()

bytecode = list(Compiler(tree).compile())

interpreter = Interpreter(bytecode)

interpreter.interpret()

return interpreter.stack.pop()I also changed the other tests so that they make use of this helper function.

Recap

In this article we didn't add a great deal of functionality to our language. However, we've made very significant progress because the parser, the compiler, and the interpreter, have now been designed in their "final" form.

As far as the parser is concerned, recall that we:

- talked about language grammars;

- wrote down the language grammar for our subset of Python; and

- refactored the parser to mimic the structure of the grammar.

Then, when we looked at the compiler and the interpreter. We used the visitor pattern to decouple the arbitrary complexity of a parsed tree from the much simpler problem of compiling a single tree node. We also used the visitor pattern to decouple the interpretation of an arbitrary sequence of bytecode operations from the much simpler problem of interpreting a single bytecode.

You can get the code for this article at tag v0.3.0 of this GitHub repository.

Next steps

The immediate next steps will still revolve around arithmetic (I promise we're almost done with this!). Adding support for some more arithmetic operators will help us get a better feel for how we should expand our language grammar.

The exercises below will challenge you to try and implement a couple of features that we will implement next, so go ahead and take a look at those.

Exercises

These two exercises are repeat exercises from the previous article. However, given your new knowledge and the new structure of the parser, compiler, and interpreter, it should be easier to tackle these now:

- Add support for the unary operators

-and+. - Add support for parenthesised expressions.

- Add support for more binary operators:

*,/,//,%,**, ... (We'll implement*,/,%, and**, in the next article. Feel free to implement even more!)

As a hint, you may want to re-read the small section about how the grammar rules everything.

Become the smartest Python 🐍 developer in the room 🚀

Every Monday, you'll get a Python deep dive that unpacks a topic with analogies, diagrams, and code examples so you can write clearer, faster, and more idiomatic code.