Problem statement

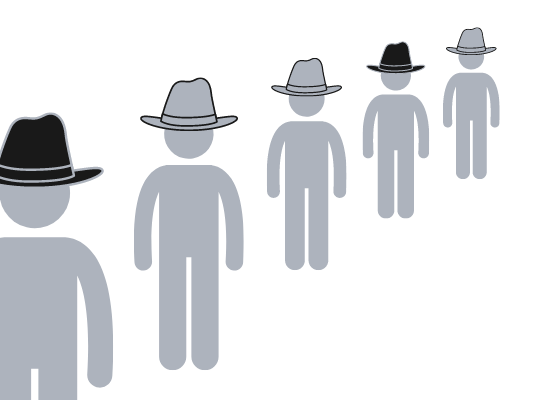

Some people, let's say \(n\) people, are standing in a line. (Of course they are more than 2m away from each other, social distancing has to be taken seriously by all of us.)

Each person has a hat, like the picture above shows. Each hat is either light or dark, but no one knows the colour of their own hat and people can only look forward and cannot move at all. (Except perhaps to blink and to breath.)

Assuming they got a chance to meet before they got placed in a line and received their hats, what strategy do they have to agree on so that the most people can guess their own hat colour correctly? We can pretend that people who fail to guess their hat colour are sent to prison, and of course we want to keep as many people out of prison as possible. The only thing they know is that the hats will be distributed randomly, they have no idea how many hats of each colour will be distributed.

So your task is to devise the best possible strategy and to find out how many people that strategy saves, on average.

It is important to note that:

- people cannot communicate with each other once they are in a line;

- they can try to guess the colours of their hats in any order you see fit;

- each person gets a single attempt;

- everyone hears everyone's guess, but only the people behind the person making a guess know if that person got it right. Everyone else has no idea if the guess was correct or not.

Give it some thought...

If you need any clarification whatsoever, feel free to ask in the comment section below.

This problem was posed to me by my friend LeafarCoder.

Solution

Let us say there's \(n\) people standing in the line. We will show that the best strategy always saves \(n - 1\) people and that the \(n^\text{th}\) person is saved with a \(50\%\) probability.

In order to do this, we have to do two things:

- Show there is no strategy with a better success rate.

- Show there is a strategy with this success rate that works.

In approaching problems of this type, where one has to “find the best strategy possible”, my approach is often one of a wishful thinker. If someone poses a problem like this, usually it's because there is an amazing strategy with a very good success rate. When that is the case, I always try to see if there can be a perfect strategy. More often than not, there is a perfect strategy or one that comes quite close to it.

For this particular problem, it is easy to see there cannot be a truly perfect strategy: the first person that guess their own hat will have no information whatsoever. Other than the colours of the hats of the other people, of course, but those are completely independent from the colour of their own hat. This means the first person will never be able to do better than randomly guessing, which has a \(50\%\) success rate.

It is after the first person guesses their hat that things get interesting, because the person that guesses first can use their guess to convey some information to the other \(n - 1\) people and, if we do this right, that information can help the next people to guess their hat correctly.

I'll show you how to do this. To make explaining the strategy simpler, let us identify dark hats with the number \(1\) and light hats with the number \(0\).

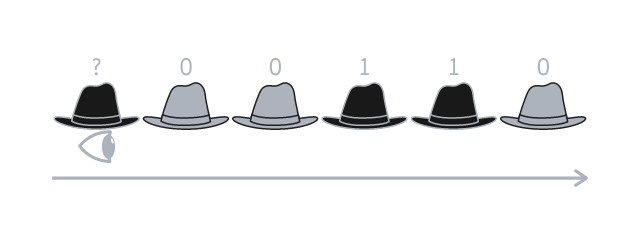

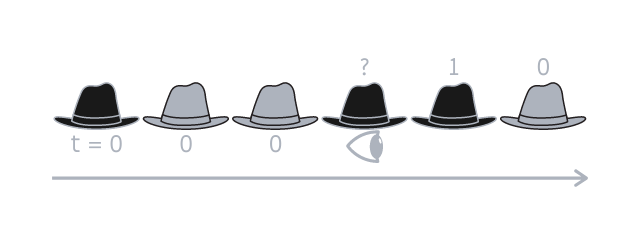

The first person that will say something will be the one at the end of the line, as that is the person that has more information available, because they can see everyone else in the line. Let me illustrate the explanation with an example, assuming \(n = 6\) and that the hats are \(1~0~0~1~1~0\), assuming the first person (the person that sees everyone) has the black hat represented by the first \(1\) from before.

The first person thus knows that the hats are distributed like this \(?~0~0~1~1~0\), with the only unknown being their own hat.

The first person will then sum the value of every hat in front of them, which would be \(2\) in this case, and check the parity of that number (i.e. answer the question “is the number even or odd?”). \(2\) is even, of course.

The first person is then tasked with letting the others know what is the parity of what their hats add up to, so that like a domino all of them guess their hats correctly.

In our example, \(2\) is even and so the first person guesses that their hat is light-coloured, because that is the colour associated with \(0\). (Unfortunately, this is one of the cases where the first person doesn't make it but their sacrifice saved everyone else!) After that, the second person in line knows that their hat, plus the others in front of them, have a specific parity.

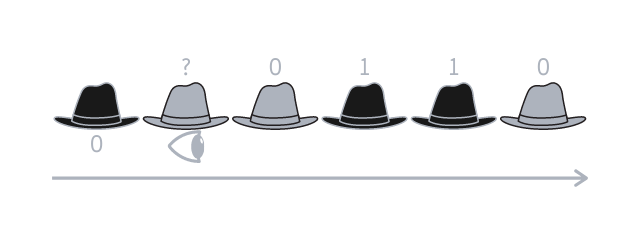

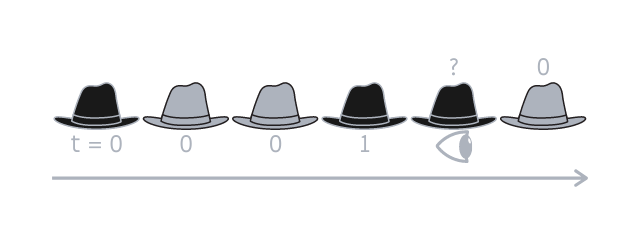

The second person can see \(n - 2\) hats and knows their parity. On top of that, the second person knows what is the parity of the \(n - 1\) hats, because the first person told them that. This means that the second person can know the parity of its own hat. In our example, the second person sees hats that sum to \(2\), which is even, and they also know that \(2\), plus their hat, should give an even number. The second person concludes that their hat is represented by \(0\) and is thus light-coloured.

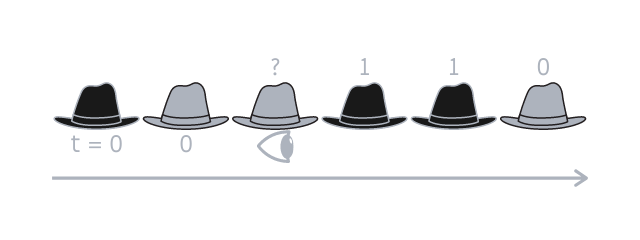

Then the process is repeated. Let us prove with induction that this works well. We will prove that if persons \(2, 3, \cdots, k\) get it right, then so does the \((k + 1)^\text{th}\) person, where the base case is for \(k = 2\). The base case was already proven, so we are left with the induction step.

Let \(h_i\) represent the number associated with the hat owned by person \(i\). In our example we have \(h_1 = h_4 = h_5 = 1\) and \(h_2 = h_3 = h_6 = 0\). Our induction hypothesis tells us that we know the values of \(h_2, \cdots, h_k\) (because those people guessed their hats correctly) and that we also know the parity of \(t = h_2 + h_3 + \cdots + h_n\), because the parity of \(t\) is the hint that the first person gives us. Finally the \((k + 1)^\text{th}\) person can see, with their own eyes, the values of \(h_{k+2}, \cdots, h_n\). In essence, \(t\) is the sum of \(n - 1\) variables and person \(k + 1\) knows \(n - 2\) of those values, meaning they can determine \(h_{k+1}\):

\[ t - \left(h_2 + \cdots + h_k \right) - \left(h_{k+2} + \cdots h_n \right) = h_{k+1} \text{ mod } 2\]

Of course we can only do this \(\text{mod } 2\) because we can only work with parities, but that is enough.

This is the proof that the strategy works. I will now complete the example we had been going over.

The third person knows the hats are like this: \(?~0~?~1~1~0\) and knows that \(0~?~1~1~0\) should add up to something even.

The third person can then guess their hat is light-coloured, because \(0~+~? + 1 + 1 + 0\) only adds up to something even if their hat (the \(?\)) is \(0\).

Next is the fourth person, that knows the hats are like this: \(?~0~0~?~1~0\) and knows that \(0~0~?~1~0\) should add up to something even.

The fourth person can then guess their hat is dark-coloured, because \(0 + 0~+~? + 1 + 0\) only adds up to something even if their hat is \(1\).

Next is the fifth person, that knows the hats are like this: \(?~0~0~1~?~0\) and knows that \(0~0~1~?~0\) should add up to something even.

The fifth person can then guess their hat is dark-coloured, because \(0 + 0 + 1~+~? + 0\) only adds up to something even if their hat is \(1\).

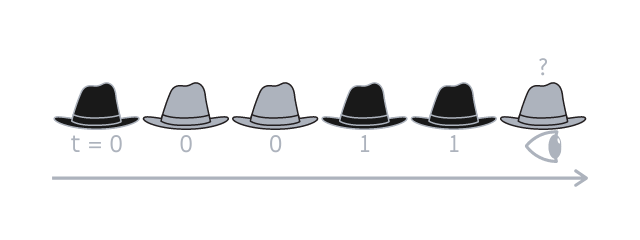

Next is the sixth, and final, person, that knows the hats are like this: \(?~0~0~1~1~?\) and knows that \(0~0~1~1~?\) should add up to something even.

The last person can then guess their hat is light-coloured, because \(0 + 0 + 1 + 1~+~?\) only adds up to something even if their hat is \(0\).

And that is it! I hope my explanation was clear!

Don't forget to subscribe to the newsletter to get bi-weekly problems sent straight to your inbox and to add your reaction below.

Become the smartest Python 🐍 developer in the room 🚀

Every Monday, you'll get a Python deep dive that unpacks a topic with analogies, diagrams, and code examples so you can write clearer, faster, and more idiomatic code.