Multi-channel transposed convolution

After having learned about transposed convolutions, I needed to see if I could understand how these convolutions work when they have multiple input and output channels. After all, when used in convolutional neural networks, they typically accept multiple input channels and produce multiple output channels.

After giving it some thought, I knew what I expected the behaviour to be, but I still had to test it to make sure I was right.

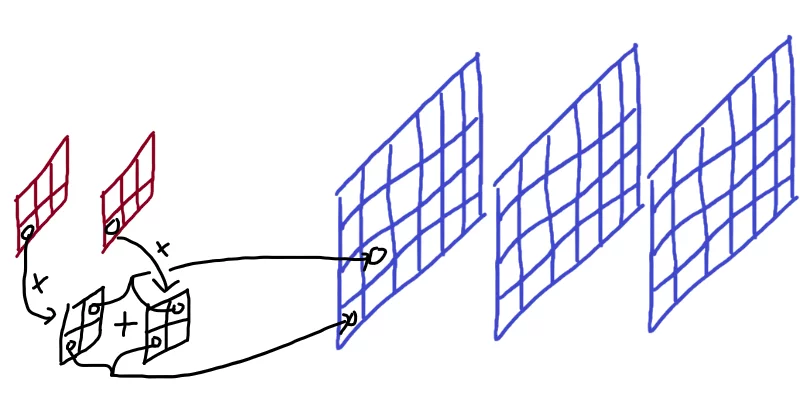

The diagram below is a representation of what I thought should happen, that I will also put in words. On the left, we have the input composed of two channels and, on the right, we have the output composed of three channels. The black arrows represent part of the work being done by the transposed convolution.

The first thing I suspected was that what I really needed was to understand how things worked for multiple input channels. My reasoning was that, whatever happens when the input has \(n\) channels and the output has 1 channel, will happen \(m\) times if the output has \(m\) channels. That's why, in the diagram above, the two rightmost output channels having nothing going on: so that we can focus on how the first output channel is built.

Then, I needed to figure out how multiple channels can be combined, in a transposed convolution, to produce one output channel.

I don't think I needed to be particularly insightful to realise only one thing made sense: for each input channel, there would be a kernel; then, each kernel would be applied to its input channel; finally, the outputs produced by each kernel would be summed up.

In order to test this theory, I resorted to PyTorch again, because they have transposed convolutions implemented. Here is the plan to test my theory:

- create a transposed convolution with 2 input channels and 1 output channel;

- create two transposed convolutions with a single input channel and a single output channel, and set their weights to match those of the first transposed convolution; and

- apply the 3 transposed convolutions and check the output of the first matches the sum of the outputs of the other two.

Start by creating the three transposed convolutions:

>>> double = torch.nn.ConvTranspose2d(2, 1, (2, 2), stride=2, bias=False)

>>> single1 = torch.nn.ConvTranspose2d(1, 1, (2, 2), stride=2, bias=False)

>>> single2 = torch.nn.ConvTranspose2d(1, 1, (2, 2), stride=2, bias=False)Notice how the shape of the weights of double is 2 1 2 2,

which we can think of consisting of 2 layers of shape 1 1 2 2,

each of those layers corresponding to single1 or single2.

Next, we set the weights of single1 and single2 to match the corresponding layer of the weights of double:

>>> with torch.no_grad():

... single1.weight[:] = double.weight[0:1]

... single2.weight[:] = double.weight[1:2]

...

>>> single1.weight == double.weight[0]

tensor([[[[True, True],

[True, True]]]])

>>> single2.weight == double.weight[1]

tensor([[[[True, True],

[True, True]]]])The with torch.no_grad() statement is just to get over a mechanism that otherwise wouldn't let us assign the kernel weights directly.

So, now we create a 2-channel input, and test my hypothesis:

>>> inp = torch.randn((1, 2, 3, 4))

>>> (double(inp) == single1(inp[0:1, 0:1]) + single2(inp[0:1, 1:2])).all()

tensor(False)Whoops! Looks like my hypothesis was wrong..? Let's look at the direct comparison:

>>> double(inp) == single1(inp[0:1, 0:1]) + single2(inp[0:1, 1:2])

tensor([[[[ True, True, True, True, False, True, False, True],

[ True, True, True, True, True, True, True, True],

[False, True, False, True, False, True, True, True],

[False, True, True, True, True, True, True, True],

[ True, True, True, True, True, True, True, True],

[ True, True, True, True, True, True, True, True]]]])Oh, ok – looks like my hypothesis is correct almost everywhere! Maybe floating point inaccuracies are too blame? After all, equality comparison with floating point numbers is always a dangerous thing. What's the largest error in these comparisons?

>>> (double(inp) - (single1(inp[0:1, 0:1]) + single2(inp[0:1, 1:2]))).max()

tensor(2.9802e-08, grad_fn=<MaxBackward1>)That's a very small number, so we can blame the error on floating point inaccuracies and conclude my hypothesis was correct!

Next up, we just need to make sure that all output channels are computed independently from each other. To do that, we run a similar experiment:

- create a transposed convolution that takes 3 channels in and outputs two channels;

- create two transposed convolutions that take 3 channels in and output one channel;

- set each of those two convolutions' kernels to match half of the kernel of the bigger convolution; and

- check that the channels produced by the big convolution match the separate channels produce by the single convolutions.

Let's do just that:

>>> double = torch.nn.ConvTranspose2d(3, 2, (2, 2), stride=2, bias=False)

>>> single1 = torch.nn.ConvTranspose2d(3, 1, (2, 2), stride=2, bias=False)

>>> single2 = torch.nn.ConvTranspose2d(3, 1, (2, 2), stride=2, bias=False)

>>> with torch.no_grad():

... single1.weight[:] = double.weight[:, 0:1]

... single2.weight[:] = double.weight[:, 1:2]

...

>>> inp = torch.randn((1, 3, 2, 4))

>>> out = double(inp)

>>> out1, out2 = single1(inp), single2(inp)Now, we check that out1 and out2 are the two layers of out:

>>> torch.allclose(

... out[0, 0],

... out1,

... )

True

>>> torch.allclose(

... out[0, 1],

... out2,

... )

TrueAbove, we use torch.allclose to work around floating point inaccuracies in checking for direct equality.

From the fact that we got two Trues,

we can see that the output channels are computed independently.

Multi-channel transposed convolution in APL

Building on the transposed convolution model from the previous article, I decided to build a model for multi-channel transposed convolution as well.

Let's play around with a transposed convolution that takes 2 channels in and outputs 3 channels,

has a 2 by 2 kernel, has no biases, and has stride 2.

For the input image, the shape will be 2 4 5.

I picked the 4 5 so that they would be different from the 2 and 3 that were already being used.

Sometimes, I make (silly) mistakes and implement things wrong,

but because too many numbers are the same, it looks like things are working...

As I realised when I started writing the code,

given the basic route I'm taking in implementing this transposed convolution,

the shape of the kernel will be 3 2 2 2,

where the initial 3 2 is the number of output channels and the number of input channels,

respectively.

Then, using the basic transposed convolution from the previous article as the basis for this multi-channel implementation,

here is what I came up with:

TC ← {⊃,/⍪⌿⍺⊂⍤×⍤2 0⊢⍵} ⍝ (inefficient) transposed convolution from previous post

mcTC ← +⌿[1]TC⍤2⍤3 ⍝ multi-channel transposed convolution

⍴ker mcTC inp

3 8 10From the code above, we can see that the shape of the final result is correct... But I don't trust my APL skills to get that right on the first try, so let's compute the first output channel “by hand” and make sure I got that right!

channel ← out[0;;] ⍝ first output channel

⍴channel

8 10

(inp1 inp2) ← ⊂⍤2⊢inp ⍝ split input channels

(⍴inp1) (⍴inp2)

┌───┬───┐

│4 5│4 5│

└───┴───┘We have the two input channels and the first output channel. Now, we just need to get the correct parts of the kernel..:

(k1 k2) ← ⊂⍤2⊢ker[0;;;]

(⍴k1) (⍴k2)

┌───┬───┐

│2 2│2 2│

└───┴───┘Now that we have all the separate parts,

we can use the function TC from the previous article to apply the transposed convolution manually:

channel ≡ (k2 TC inp2)+(k1 TC inp1)

1Hooray! Seems like we got it right!

Another multi-channel transposed convolution in APL

Working with Aaron Hsu on this, he sent me an implementation of upsampling through these transposed convolutions, and I was supposed to check his code made sense.

Here is the version he sent me:

UP ← {((2ׯ1↓⍴⍵),¯1↑⍴⍺)⍴0 2 1 3 4⍉⍵+.×⍺}⍵ is supposed to be the input,

whose shape is w h ic, where ic is the number of input channels;

and ⍺ is supposed to be the kernel,

with shape ic k k oc,

where k is the kernel size (we are using square kernels) and oc is the number of output channels.

Through a similar experiment as the one I did above, I checked his code made sense:

ker ← ?3 2 2 5⍴0 ⍝ 3 input channels, 5 output channels

inp ← ?13 17 3⍴0

UP ← {((2ׯ1↓⍴⍵),¯1↑⍴⍺)⍴0 2 1 3 4⍉⍵+.×⍺}

out ← ker UP inp

channel ← out[;;0] ⍝ first output channel

(inp1 inp2 inp3) ← (inp[;;0]) (inp[;;1]) (inp[;;2]) ⍝ split input channels

(k1 k2 k3) ← ⊂⍤2⊢ker[;;;0] ⍝ split kernel layers

channel ≡ (k3 TC inp3)+(k2 TC inp2)+(k1 TC inp1) ⍝ compute by hand

1 ⍝ Success!Hooray! Seems like he got it right!

That's it for now! Stay tuned and I'll see you around!

Become the smartest Python 🐍 developer in the room 🚀

Every Monday, you'll get a Python deep dive that unpacks a topic with analogies, diagrams, and code examples so you can write clearer, faster, and more idiomatic code.

References

- “TIL #033 – transposed convolution”, https://mathspp.com/blog/til/033 [last accessed 23-02-2022];