This is the written version of my PyCon Italy 2025 talk, which serves as a trial run for myself and as supporting material for folks who attended the talk, or who couldn't attend but are interested in reading about it.

Cold opening

>>> from pathlib import Path

>>> Path(".")

PosixPath('.')

>>> type(Path(".")) == Path

FalseAre you comfortable with the short REPL session from above?

Don't you think it's weird you try to create an instance of the class Path but instead you get an instance of the class PosixPath?

I mean, in your computer you might even get something different: an instance of the class WindowsPath.

Isn't it funky how the class that we get depends on your context? In this particular case, on your operating system?

Outline for this talk

I was using the module pathlib one day and I thought that this was weird, so today I will show you how this works.

Sadly for you, but thankfully for me, this is not going to be a hardcore metaprogramming talk.

After all, it is called “Dipping my toes in metaprogramming”, not “Drowing in metaprogramming”.

What this talk is, is an introduction to a very useful metaprogramming tool, that sits right on the fence between crazy, esoteric metaprogramming and general Python knowledge that is likely to help you out sooner or later.

The plan for this talk is to

- talk a little bit about parity of integers, in an attempt to show you a similar pattern that is slightly simpler;

- go back to talking about paths and the behaviour that they exhibit when instantiated;

- talk a little bit about immutability and subclassing immutable types; and

- we'll end with some time for Q|A, where you'll be able to ask questions or we'll sit together in awkward silence.

Parity

To get things rolling, we will start off by trying to emulate the instantiating pattern exhibited by Path, but with different classes.

We will create a class Number, that takes integers, and that produces one of its subclasses:

-

OddNumber, if the integer was odd; or -

EvenNumber, if the integer was even.

So, we want to build a hierarchy that looks like this:

class Number:

...

class EvenNumber(Number): ...

class OddNumber(Number): ...And the point is that, when you instantiate the class Number, you get an instance of EvenNumber or OddNumber, depending on the parity of the argument:

print(type(Number(2))) # <class '__main__.EvenNumber'>Now, when trying to solve this problem, you might start by writing this code:

class Number:

def __init__(self, value):

...

class EvenNumber(Number): ...

class OddNumber(Number): ...And now you're thinking “What the hell do I write in Number.__init__?”.

But, the truth is...

Inside Number.__init__ it's already too late for whatever you need to do!

The argument self is already a reference to an object whose type is Number and you can't “hot-swap” the type of an object during program execution!1

What's the solution, then..?

Well, one thing I like about Python is how it is so consistent in defining dunder methods that customise the whole language and the interactions with the syntax, and it just so happens that the solution to this problem lies in another dunder method!

The dunder method __init__ has the purpose of initialising your object, which for the purposes of this talk I want to refer to as “customising”.

The dunder method __init__ customises your object, performs any required setup, etc.

This implies that the object is already there to begin with.

But __init__ has a big brother!

The dunder method __new__ is the method that is responsible for bringing objects into existence!

That's the dunder method we need to implement.

We can go ahead and write its signature:

class Number:

def __new__(...):

...And immediately we face a challenge?

What are the parameters of __new__?

Since, when we run __new__, the instance hasn't been created yet, there's no way the first argument is self.

That's nonsensical.

In fact, the first parameter is cls, the class we are trying to create an instance of:

class Number:

def __new__(cls, ...)

...Next, whatever arguments you pass when creating your instance also get passed to __new__.

In other words, if you want to be able to write something like Number(3), then __new__ needs to accept that value:

class Number:

def __new__(cls, value):

...

print(Number(3))Finally, when I'm working with dunder methods I don't understand, I always like to add calls to the function print.

The whole thing with dunder methods is that they're called by Python without you having to call them, so it helps to have prints to see when your dunder methods are running:

class Number:

def __new__(cls, value):

print("Number.__new__")

print(Number(3))This code is already runnable, although it may produce results that you find unexpected:

Number.__new__

NoneWe can see that the dunder method __new__ ran when we instantiated Number, but then when we print Number(3), we see None...

And that is because __new__ is supposed to return something!

What's that something?

It could be anything!

class Number:

def __new__(cls, value):

print("Number.__new__")

return 73

print(Number(3))Running this code, you get a 73:

Number.__new__

73__new__ can return anything you want, but typically you want it to return an instance of the class you are trying to instantiate.

Remember?

That's the whole point.

Great.

But how?

When you instantiate a class, like with Number(3), you want to create a new instance.

So, Python calls Number.__new__.

Now, inside Number.__new__, you need to create a new instance!

This feels like the chicken-and-egg problem:

you need __new__ to create the new instance, but somehow you need to create the new instance inside __new__.

The solution?

Pass the responsibility to someone else through super():

class Number:

def __new__(cls, value):

print("Number.__new__")

return super().__new__(cls)

print(Number(3))You call the method __new__ on the superclass, but you pass in the “current” class to make sure the new object is created with the correct type.

If you run this code now, you see that you get an instance of the class Number, which is what you wanted all along:

Number.__new__

<__main__.Number object at 0x10027a900>Now, there is another interesting thing to consider, here.

That is the fact that you have a lot of flexibility with respect to what goes inside super().__new__(...).

Take a look at this short REPL interaction:

>>> class C: ...

...

>>> object.__new__(C)

<__main__.C object at 0x102bb46e0>Note how I created a class C, asked object to create a new object of type C, and object just abided by my wishes.

In case it wasn't clear, what this is showing is that the class cls you pass into super().__new__ actually determines the type you get back.

Therefore, going back to the problem of getting an instance of EvenNumber or OddNumber boils down to swapping cls inside Number.__new__ depending on the parity of the argument:

class Number:

def __new__(cls, value):

if cls is Number:

cls = OddNumber if value % 2 else EvenNumber

return super().__new__(cls)

class OddNumber(Number): ...

class EvenNumber(Number): ...

print(Number(3))Running this code, you finally get an instance of OddNumber when you instantiate Number:

<__main__.OddNumber object at 0x1009a6900>Now, what if someone that's either crazy or very distracted tries to do something like OddNumber(42)?

If you do so, you get a mismatch between the class name and the parity of the value, so you have to protect yourself against that.

Again, OddNumber.__init__ feels semantically too late because at that point you already created the instance of OddNumber, so you can do it inside OddNumber.__new__:

class Number:

def __new__(cls, value):

if cls is Number:

cls = OddNumber if value % 2 else EvenNumber

return super().__new__(cls)

class OddNumber(Number):

def __new__(cls, value):

if not value % 2:

raise ValueError("Go drunk, you're home! 🍻")

class EvenNumber(Number): ...

print(OddNumber(42))Now, if you try to create an instance of OddNumber with an even argument, you get an exception:

# ...

ValueError: Go drunk, you're home! 🍻At this point, you can stand back and rejoice, since you're already implemented the instantiation pattern that pathlib.Path implements!

In fact, you can quickly mock it up following the same structure as for Number / OddNumber / EvenNumber.

Paths

Since I can't switch operating systems in the middle of the talk, we'll pretend that the global variable _OS controls the operating system I'm running on:

_OS = "Windows"

class Path:

def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs):

if cls is Path:

cls = WindowsPath if _OS == "Windows" else PosixPath

return super().__new__(cls)

class WindowsPath(Path):

def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs):

if _OS != "Windows":

raise RuntimeException("Nope.")

class PosixPath(Path):

def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs):

if _OS == "Windows":

raise RuntimeException("Nope.")With this code, you can already create the correct instances of your paths:

# ...

_OS = "Windows"

print(type(Path("."))) # <class '__main__.WindowsPath'>If you swap the operating system, you get instances of the other type of path:

# ...

_OS = "Linux"

print(type(Path("."))) # <class '__main__.PosixPath'>And this is exactly the code that the standard library module pathlib implements!

The code shown below is copied verbatim from Python 3.14's branch:

class Path(PurePath):

# ...

def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs):

if cls is Path:

cls = WindowsPath if os.name == 'nt' else PosixPath

return object.__new__(cls)

# ...

# ...

class PosixPath(Path, PurePosixPath):

# ...

if os.name == 'nt':

def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs):

raise UnsupportedOperation(

f"cannot instantiate {cls.__name__!r} on your system")

class WindowsPath(Path, PureWindowsPath):

# ...

if os.name != 'nt':

def __new__(cls, *args, **kwargs):

raise UnsupportedOperation(

f"cannot instantiate {cls.__name__!r} on your system")Ok, I lied.

It isn't exactly the same, for two reasons.

First, the module pathlib swaps the order of the definition of __new__ and the conditional check, but that's not very important.

Second, the three classes in pathlib inherit from other classes, and that touches on something that we didn't talk about yet.

And that is the interaction between __new__ and __init__!

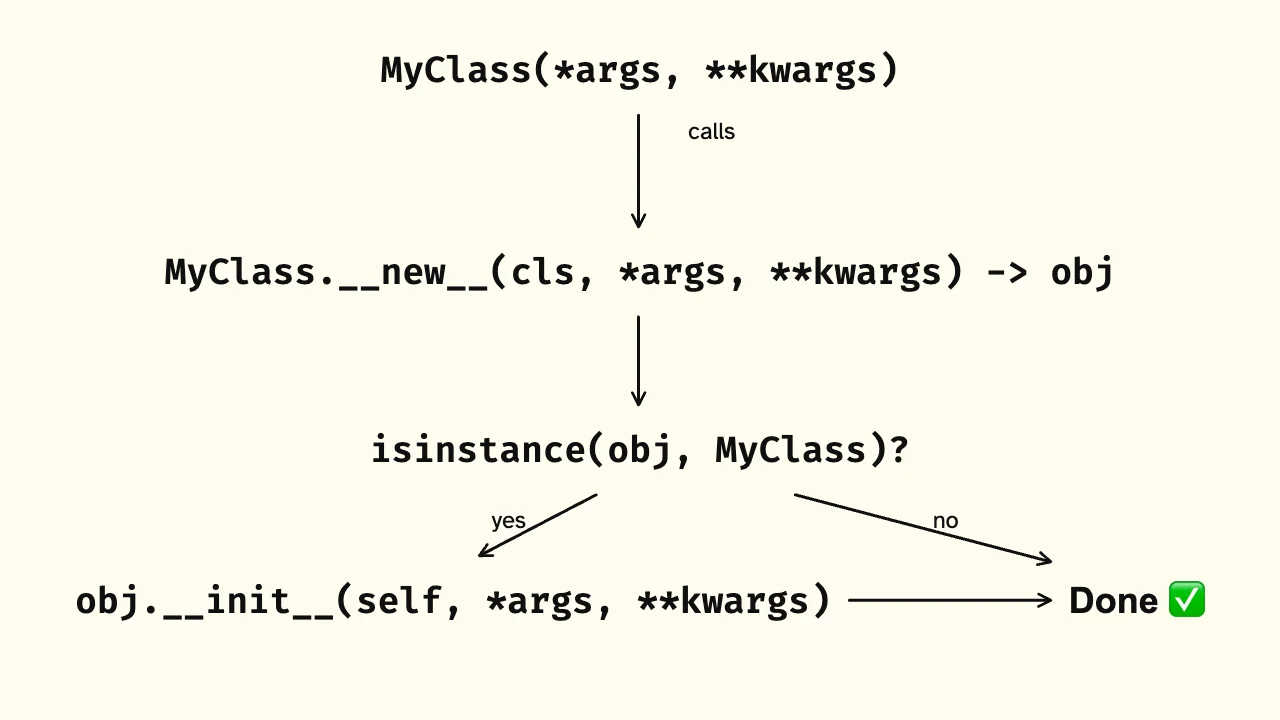

When you instantiate a class MyClass, Python will try to call MyClass.__new__.

If it's not there, it goes up the class hierarchy looking for a __new__.

(Eventually, it'll find one in object.__new__.)

After finding a __new__, Python calls it and looks at the return value.

If the return value obj is an instance of MyClass, then Python will try to call obj.__init__.

As a diagram, if MyClass.__new__ exists, the flow looks like this:

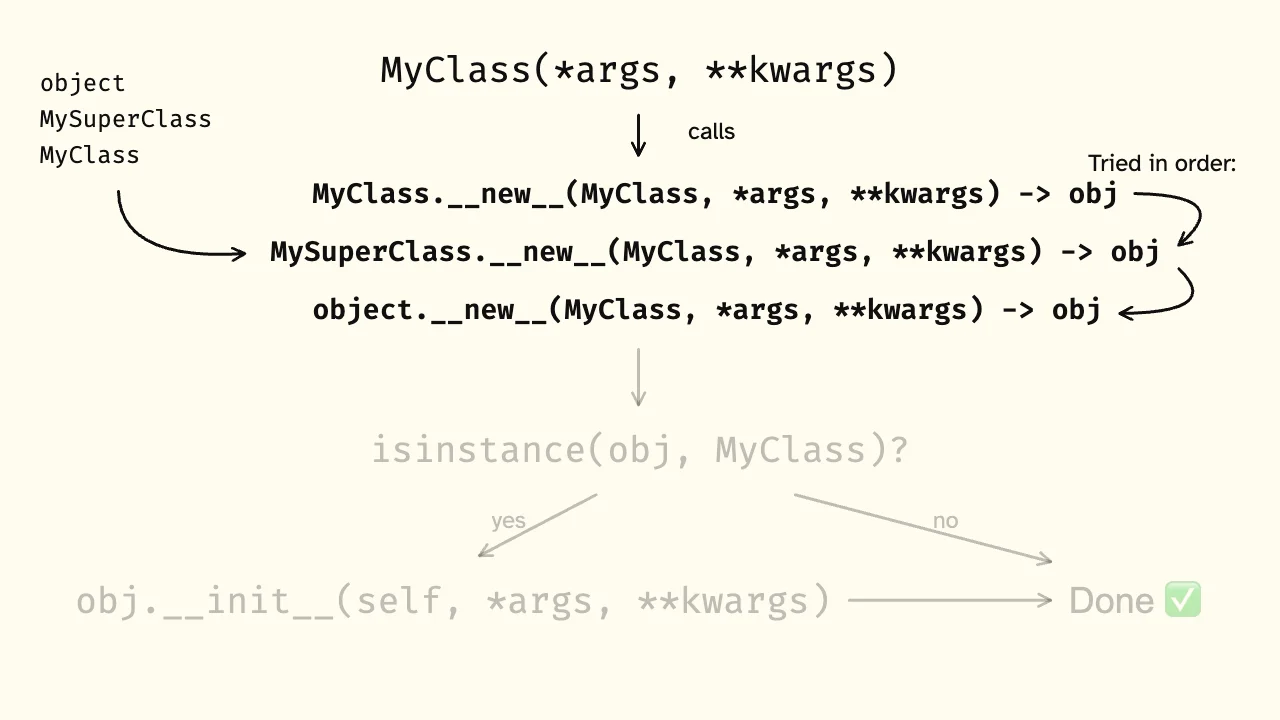

In reality, Python will try to call a dunder method __new__ with cls set to MyClass, and it will look up the hierarchy if necessary:

Immutability

Now that you've seen the dunder method __new__ being used twice, I will show you a different application of it.

As it turns out, if you want to subclass an immutable type, you need to use __new__.

The “why” is “easy” to understand. Just consider the following REPL session:

>>> my_list = [42, 73, 0, 16, 10]

>>> print(id(my_list))

4376165376

>>> my_list.__init__(range(3))

>>> print(id(my_list))

4376165376

>>> print(my_list)

[0, 1, 2]As the example shows, by calling __init__ on a list after creating it I'm able to mutate the values of the list.

However, it's important to note that I am mutating the list and not creating a new one, as shown by the fact that the id of the list is preserved.

On the other hand, if I'm working with an immutable type, then the dunder method __init__ won't do anything.

If it did, then the type wouldn't be immutable in the first place:

>>> f = float(3.14)

>>> f.__init__(0.5)

>>> f

3.14With that out of the way, I just want to take a moment to appreciate how annoying floats are:

print((1 / 729) * 729 == 1)

# FalseNow that we're equipped with a shiny new hammer, let's fix this!

We'll implement a class TolerantFloat that performs equality comparisons with a relative error tolerance.

Since I want the class TolerantFloat to be a subclass of float, so that all other behaviour is inherited, I need to implement the dunder method __new__:

class TolerantFloat(float):

def __new__(cls, value, rel_tol):

return super().__new__(cls, value)

def __init__(self, value, rel_tol):

self.rel_tol = rel_tolTo finish this off, I need to implement the dunder method __eq__ using the relative error tolerance.

It's beside the point of this talk, but I will implement it for the sake of completeness and so that we can test it:

import math

class TolerantFloat(float):

def __new__(cls, value, rel_tol):

return super().__new__(cls, value)

def __init__(self, value, rel_tol):

self.rel_tol = rel_tol

def __eq__(self, other):

if isinstance(other, int | float | TolerantFloat):

return math.isclose(self, other, rel_tol=self.rel_tol)

return NotImplemented

tf = TolerantFloat(3.14, 0.01)

print(tf == math.pi) # TrueSubclassing immutable types is a good example use-case for the dunder method __new__.

Conclusion

In this talk you've been exposed to the dunder method __new__.

You've seen how it works and a couple of code examples making use of the dunder method __new__.

However, metaclasses were nowhere to be found...

If you ever need metaclasses, you will find that there is a huge change you'll be using the dunder method __new__.

When that time comes, you will remember me and thank me for having taught you how __new__ works, because learning about __new__ while grappling with metaclasses isn't fun for anyone.

As a quick recap, this talk tried to teach you that __new__:

- brings class instances into existence;

- returns whatever you want;

- determines whether

__init__runs or not; and - is usable for dynamic instantiation patterns.

As a side effect, I only learned these things and I only gave this talk because I was using pathlib, a module I use very frequently, and suddenly I stopped in my tracks and wondered how the module worked.

There are many modules in the standard library that are implemented in Python and you stand to learn a lot if you browse their source code.

If you're interested in metaprogramming and my talk left you longing for more, I can recommend you check the module enum, which relies on metaprogramming techniques and tools.

Thank you very much for your attention!

Q|A

If you're reading this, you can ask me questions by emailing me or by finding me on any of the social media I have a presence on.

Thank you for watching!

If you watched my talk, please fill this feedback form. It really helps me to know how to improve my talks.

If you really enjoyed my talk, you are also welcome to leave a written testimonial so I can brag about it online! 🚀

Finally, if you're interested in becoming a better Python dev, take a look at the Python drops 🐍💧 newsletter. Each day, I send a short and actionable Python tip to make sure your skills don't stagnate!

P.S. This talk was inspired by this article about the dunder method __new__.

There is a lot of overlap with the linked article but you will still benefit from going over it, as it will help solidify the concepts.

-

I mean, maybe you can..? Python is a very dynamic language, so there may be some super dark wizardry that allows you to do this? In other words, I can't prove that it is absolutely impossible. But if it's possible, it's much more complicated than what we're about to do either way! 🤣 ↩

Become the smartest Python 🐍 developer in the room 🚀

Every Monday, you'll get a Python deep dive that unpacks a topic with analogies, diagrams, and code examples so you can write clearer, faster, and more idiomatic code.

References

- “Customising object creation with

__new__”, mathspp blog, https://mathspp.com/blog/customising-object-creation-with-__new__ [last accessed 30-05-2025];