Preamble

In this article, we will use Python to reimplement the built-in enumerate.

We will start with a rough solution that doesn't really cut it,

and we will rework it bit by bit until we have a full reimplementation of the built-in enumerate.

We will use this task as the motivation for studying a series of interesting Python concepts and subtleties.

As a by-product of working through this article,

you will also gain a better understanding of what the built-in enumerate is and how it really works.

After you work through this article, you will:

- understand what the built-in

enumerateis and how it works; - be able to point practical differences between generic iterables and lists;

- know what (lazy) generators are;

- understand the relationship between

zipandenumerate; - have used the keywords

yieldandyield from; - know the difference between

yieldandyield from; - be acquainted with infinite generators; and

- have a full reimplementation of

enumeratein Python.

This article is also the written version of a talk I gave at PyCon Sri Lanka 2022. The talk slides are available here and the YouTube recording is here.

Introduction

Imagine you have a string:

s = "hey"How would you go about printing each character of that string? The typical beginner loop would look like this:

for idx in range(len(s)):

print(s[idx])r

o

dHowever, beginners soon learn about the power of iterables, which lets them write the previous loop in a more explicit and expressive way:

for char in s:

print(char)r

o

dNotice how we get to give a name (char) to each element of the string,

instead of having to use the integer idx to index into the string.

This is possible because strings are iterables:

objects that can be traversed;

objects for which we can get their items one by one, in a loop.

Now, imagine that you wanted to print each letter and its index, instead of just printing the characters. How would you go about doing that?

Perhaps you'll suspect you need to go back to using the range of the length of s:

s = "rod"

for idx in range(len(s)):

print(f"Letter {idx} is {s[idx]}")Letter 0 is r

Letter 1 is o

Letter 2 is dAnd yet, Python provides a built-in that lets us do this while writing the for loop in an expressive manner,

just like before.

In order to do that,

we use the built-in enumerate,

which gives us access to the successive elements and their indices:

s = "rod"

for idx, letter in enumerate(s):

print(f"Letter {idx} is {letter}")Letter 0 is r

Letter 1 is o

Letter 2 is dAgain, notice how enumerate allowed us to write such an expressive loop that clearly communicates our intent:

we want to use the indices (idx) and the letters (letter).

In this article,

we will look at the built-in enumerate and we will try to implement it.

We will start with a simple model of enumerate that we will refactor bit by bit,

fixing its behaviour and improving the quality of its code.

A first stab

Before writing our very first reimplementation of the built-in enumerate,

it might be a good idea to actually see what it is that enumerate produces.

I mean, we know it gives us indices and items,

because that's what we get in the for loop...

But where do those indices and items come from?

Instead of writing for idx, letter in ... in the loop,

we will write for element in ... and then we will print that,

to see what it is that we get:

for element in enumerate(s):

print(element)(0, 'r')

(1, 'o')

(2, 'd')As we can see, enumerate produces tuples with two elements:

- the index; and

- the corresponding item of the iterable.

It is also noteworthy that enumerate(s) is also an iterable...

After all, we wrote a for loop that is traversing enumerate(s)

and printing its elements, one at a time!

Given that the elements of enumerate(s) seem to be tuples,

maybe we could start there.

What “simple” object could replace the ... below

that would give the same output?

for element in ...:

print(element)(0, 'r')

(1, 'o')

(2, 'd')A possibility would be a list with all the tuples:

for element in [(0, 'r'), (1, 'o'), (2, 'd')]:

print(element)(0, 'r')

(1, 'o')

(2, 'd')Maybe we can implement our enumerate to return a list with the tuples...

>>> enumerate_("rod")

[(0, 'r'), (1, 'o'), (2, 'd')]For that, let's use a for loop that populates a list with these tuples,

and then we return the list:

def enumerate_(iterable):

result = []

idx = 0

for elem in iterable:

result.append((idx, elem))

idx += 1

return resultThis is a helpful model of enumerate because it gives some insight into the dynamics of it,

but it's not a very accurate model...

In order to understand why,

we need to talk about generators.

Lazy generators

Quick! What Python code would produce the following list:

>>> ...

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]If you thought about range(10),

you are close!

Wrong, but close.

Let me show you that range(10) does not produce those ten integers:

>>> range(10)

range(0, 10)By itself, range doesn't produce the numbers we wanted, but why?

Because range is a generator.

Generators are Python objects that know how to produce a succession of values,

but only do so when the values are needed.

For example, range(10) knows exactly how to generate the numbers zero through ten,

but because you haven't needed them yet,

range hasn't actually gone through the trouble of showing them to you.

If you really want to see the numbers,

you can put a call to list around range:

>>> list(range(10))

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]list has this effect because list needs the values from the range,

otherwise it couldn't build a list out of them!

Coincidentally,

enumerate also produces these (lazy) generators that don't do much by themselves:

>>> enumerate("rod")

<enumerate object at 0x000001F616DE4540>If you want to see the elements that a particular enumerate object will produce,

just wrap the enumerate object with a call to list:

>>> list(enumerate("rod"))

[(0, 'r'), (1, 'o'), (2, 'd')]I haven't told you yet, but the brilliance of generators is that they can give you one element at a time! That is why generators are useful: they are said to be lazy because they compute one item at a time, and they only compute items when they are needed! In situations where you don't need all the items, generators save time because they didn't do all the computations beforehand.

So, how do we refactor enumerate_ to return the elements one at a time?

How do we embed our enumerate_ with this laziness?

What we wish we could do is something like this:

def enumerate_(iterable):

idx = 0

for elem in iterable:

return idx, elem

idx += 1However, we know that the return leaves the function,

returning the value in front of it.

In our case, that would be a tuple (0, elem),

where elem would be the very first element of the iterable:

>>> enumerate_("rod")

(0, 'r')What we wanted was for that “return” to not be permanent: to give back that piece of information, but in a way that lets the function produce the next element. And the next. And the next.

return doesn't work because it is a keyword that has a very specific meaning,

so perhaps we could use another keyword?

With a keyword like that,

our code would look like this:

def enumerate_(iterable):

idx = 0

for elem in iterable:

<lazy-result-keyword> idx, elem

idx += 1Again, the idea is that <lazy-result-keyword> means something like

“return this value for now and come back because I may have more values for you”.

The keyword that we are looking for is yield:

def enumerate_(iterable):

idx = 0

for elem in iterable:

yield idx, elem

idx += 1Using this keyword means that enumerate_ is now lazy and doesn't return all the results at once.

We can verify this by calling it:

>>> enumerate_("rod")

<generator object enumerate_ at 0x000001BAB7372D60>The REPL now says that we have a generator object, which is Python's way of telling us we have an object that generates values lazily!

Much like with the built-in enumerate,

if we want to see all of the elements of the result,

we can wrap the call to enumerate_ in a call to list:

>>> list(enumerate_("rod"))

[(0, 'r'), (1, 'o'), (2, 'd')]Our enumerate_ now produces generators,

like enumerate does,

but we still have an inaccurate implementation.

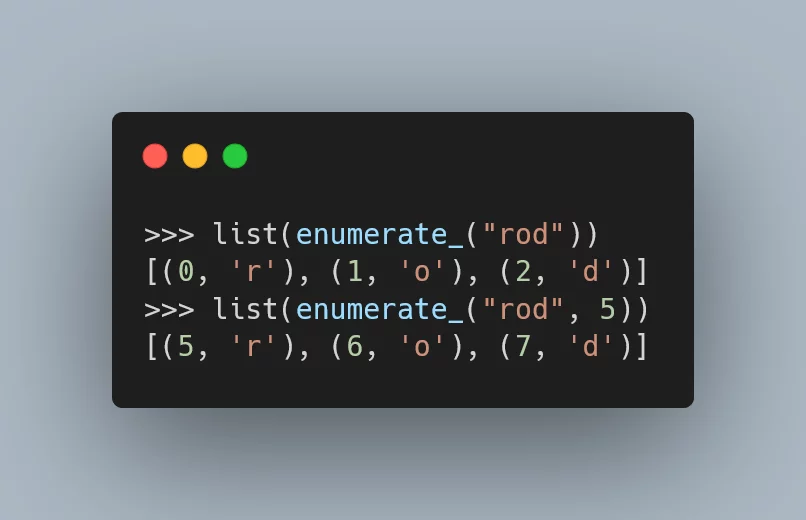

Optional parameter start

The next thing that needs to be done is to make sure that enumerate_ has all the features that the built-in enumerate has.

In this case, that means we need to implement the optional parameter start,

that we haven't taken a look at yet.

As we have seen before,

when we give an iterable to enumerate,

it just builds tuples with indices and the elements of the iterable,

and the indices start from zero:

>>> list(enumerate("rod"))

[(0, 'r'), (1, 'o'), (2, 'd')]However, enumerate accepts a second argument that specifies a different starting point for the counting:

>>> list(enumerate("rod", 5))

[(5, 'r'), (6, 'o'), (7, 'd')]This second argument is typically called start.

In order to implement this functionality,

we need to add a second parameter to our enumerate_.

Then, we initialise the value of the index with the argument that is passed in:

def enumerate_(iterable, start=0):

idx = start

for elem in iterable:

yield idx, elem

idx += 1Let's take it for a spin:

>>> list(enumerate_("rod"))

[(5, 'r'), (6, 'o'), (7, 'd')]At this point,

we have a simple piece of code that appears to have all the features of enumerate,

so we are done, right?

No! Let's see if we can improve this piece of code.

Bookkeeping the indices

When I am looking at a piece of code that I want to refactor, one of the things I look out for is code that isn't algorithmically relevant, but that is needed for the whole thing to work.

I look for those pieces of code, and then I investigate whether or not I can refactor my code to take care of that piece of code in a more elegant way. Sometimes I know how to do that; other times, not so much.

In the function enumerate_ above,

one such piece of uninteresting – but necessary – code is the variable idx.

Notice that idx is very predictable:

its starting value is start,

and then its value is incremented for every element of the iterable we go through:

def enumerate_(iterable, start=0):

idx = start # <- Initialisation.

for elem in iterable:

yield idx, elem

idx += 1 # <- (Predictable) Increment.Take an example we've looked at before:

>>> list(enumerate_("rod"))

[(5, 'r'), (6, 'o'), (7, 'd')]Now, look at the numbers being used,

which were produced by idx.

How could we generate them?

>>> list(enumerate("rod", 5))

[(5, 'r'), (6, 'o'), (7, 'd')]

>>> ...

[5, 6, 7]This time, you probably guessed it right!

With a list(range(...)):

>>> list(enumerate("rod", 5))

[(5, 'r'), (6, 'o'), (7, 'd')]

>>> list(range(5, 5 + 3))

[5, 6, 7]The built-in range can do exactly what idx has been doing:

it can have a specific starting value,

and then it gives us successive numbers with increments of one unit.

Using range to do the bookkeeping of the indices looks like a great idea,

we just need to be able to determine the arguments that we pass in to the call to range.

The starting value should be the same as the start value of the enumerate.

As for the stopping value,

it should be the starting value plus the length of the iterable.

That's why, in the example above,

the second argument to range was 5 + 3:

the + 3 referred to the fact that "rod" has three characters.

Now that we have a better way of doing the bookkeeping of the indices,

we need to go through the iterable and the range at the same time,

so that we can yield the indices and the elements at the same time:

def enumerate_(iterable, start=0):

idxs = range(start, start + len(iterable))

for i in range(len(iterable)):

yield idxs[i], iterable[i]But wait!

Didn't you pay attention in the beginning?

Python's for loops are amazing and range(len(...)) is typically NOT what you want to use in a for loop.

Currently, our for loop is using an index i to be able to traverse the range idxs and the iterable at the same time.

However, there is a built-in tool that serves that purpose,

and it is called zip!

It allows you to go through two (or more) iterables at the same time.

Let me show you:

>>> list(zip(range(3), "rod"))

[(0, 'r'), (1, 'o'), (2, 'd')]By the way,

can you guess why it is that we need the call to list wrapping zip?

It's because zip also produces generators!

Knowing that we can use zip to put the indices and the elements together,

we can rewrite our code to look something like this:

def enumerate_(iterable, start=0):

idxs = range(start, start + len(iterable))

for idx, elem in zip(idxs, iterable):

yield idx, elemAt this point,

we have introduced the idiomatic for loop that uses zip to indicate that two iterables are connected,

in the sense that we want to traverse both at the same time.

However, now we will see that the right instinct led to the wrong execution.

Iterables, not sequences

Notice how enumerate_ already works with many different types of iterables:

>>> list(enumerate_("rod"))

[(0, 'r'), (1, 'o'), (2, 'd')]

>>> list(enumerate_(["hello", "world", "!"]))

[(0, 'hello'), (1, 'world'), (2, '!')]

>>> list(enumerate_(range(0, 30, 10)))

[(0, 0), (1, 10), (2, 20)]This is a nice property:

as long as the argument to enumerate is something that we can traverse (i.e., is iterable),

enumerate will know what to do with it.

However, if we look closely enough, we will notice the arguments we used above all have a length:

- the string

"rod"has length 3; - the list

["hello", "world", "!"]has length 3; and - the range

range(0, 30, 10)has length 3.

I don't mean these objects “have length 3” because I can count the elements.

I'm saying these objects “have length 3” because you can use the built-in len on them:

>>> len("rod")

3

>>> len(["hello", "world", "!"])

3

>>> len(range(0, 30, 10))

3However, our enumerate_ isn't complete!

You can use enumerate on zip:

>>> firsts = ["Harry", "Ron", "Hermione"]

>>> lasts = ["Potter", "Weasly", "Granger"]

>>> list(enumerate(zip(firsts, lasts)))

[(0, ('Harry', 'Potter')), (1, ('Ron', 'Weasly')), (2, ('Hermione', 'Granger'))]But you can't use enumerate_ on zip:

>>> list(enumerate_(zip(firsts, lasts)))

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

File "<stdin>", line 2, in enumerate_

TypeError: object of type 'zip' has no len()The error message is pretty clear about the issue:

we cannot use the built-in len on zip objects.

The overarching problem?

enumerate is supposed to work on any iterable,

but we made it so that it only works on iterables that have a length!

So, when I encounter an issue,

first I like to think about how I got there:

where are we using len, and why?

If you recall,

we are hitting this problem because we are using the built-in len to determine how long the range object for the indices should be...

However, as we've seen,

some iterables don't know their length!

Therefore, we can't use range to generate our indices because range needs to know its stop argument,

and we can't always tell when we'll be stopping...

Could we generate the indices in some other way..? Yes we can! We can write our own generator for the indices! It starts at the given value, and then yields consecutive numbers after that! But when should it stop..?

Not all good things need to end

We ran into an issue because we tried to specify when range stopped,

so we need to work around that issue.

We do that by creating a generator that never stops!

Hence, our index generator could look like this:

def gen_indices(start):

idx = start

while True:

yield idx

idx += 1If you are anything like me,

the first thing you'll do after defining gen_indices is create a loop that goes through the indices and prints them:

>>> for idx in gen_indices(0):

... print(idx, end=" ")

...

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 2, in <module>

KeyboardInterruptRecall that you can stop an infinite loop by pressing Ctrl + C!

This make it look like our index generator isn't very useful on its own... But it can be! It just depends on how you use it.

This might be a good time to introduce you to the built-in next,

a very handy built-in for when you are working with generators, and iterators in general.

The built-in next does what it says on the tin:

given an iterator,

returns the next item of that iterator.

Oversimplifying,

we can say that next can be used to fetch the next item of a generator.

So, we can use gen_indices to define a generator that starts counting at, say, 42:

>>> count_from_42 = gen_indices(42)

>>> count_from_42

<generator object gen_indices at 0x00000195DE3AA890>Notice how gen_indices was actually used to create the generator object count_from_42!

This nuance can trick you some times!

Now, we want to take a look at the elements that count_from_42 produces.

Using list won't work because we can't create an infinite list!

Thus, the other option on the table is to use next to fetch consecutive elements:

>>> count_from_42 = gen_indices(42)

>>> next(count_from_42)

42

>>> next(count_from_42)

43

>>> next(count_from_42)

44

>>> next(count_from_42)

45We could use next to manage manually the generator for the indices,

but we really don't need to do that!

Because of the way zip works,

we don't need to worry about the fact that gen_indices is infinite,

because zip will stop as soon as the argument iterable is finished:

def enumerate_(iterable, start=0):

for idx, elem in zip(gen_indices(start), iterable):

yield idx, elem>>> list(enumerate_("rod", 5))

[(5, 'r'), (6, 'o'), (7, 'd')]

>>> list(enumerate_(zip(firsts, lasts)))

[(0, ('Harry', 'Potter')), (1, ('Ron', 'Weasly')), (2, ('Hermione', 'Granger'))]Again, just to help it sink in:

using gen_indices instead of range works better because gen_indices is less constrained.

In other words,

range needs to know its starting and stopping points,

whereas gen_indices only needs to know its starting point.

Bookkeeping the indices, again...

We just introduced five more lines of code, so it would be naïve of us to assume that we wrote them in the best way possible on the first try. In fact, if we look at them carefully, we can see exactly the same bookkeeping pattern we tried to get rid of before:

def gen_indices(start):

idx = start # <- set `idx`

while True:

yield idx

idx += 1 # <- always increment `idx`If you are familiar with languages like C/C++, Java, JavaScript,

or a bunch of others,

you might recognise that the yield idx; idx += 1 pattern can be replaced.

All it takes is for you to dust off that walrus operator :=.

By making use of assignment expressions,

we get to yield the value of idx and increment it at the same time.

How?

If we rewrite idx += 1 as idx = idx + 1,

we can then replace the assignment operator = with the walrus operator :=:

idx := idx + 1Ok, and so what?

idx += 1 and idx = idx + 1 are statements:

lines of code that represent an instruction that is carried out by Python.

In this case, they are assignment statements,

meaning that they assign values to variables.

On the other hand, idx := idx + 1 is an expression,

a piece of code that can be evaluated to produce a result.

Using not-so-rigorous language, the walrus operator lets us do things like “print an assignment”:

>>> x = 3

>>> print(y := x + 1)

4

>>> y

4(Of course, the example above isn't the intended use case of assignment expressions.)

Because idx := idx + 1 is an expression,

it can be used with the keyword yield to make up a yield statement:

def gen_indices(start):

idx = start

while True:

yield (idx := idx + 1)In doing so, we manage to combine the increment and the yielding into one expression... Except we are off by one, now:

>>> list(enumerate_("rod"))

[(1, 'r'), (2, 'o'), (3, 'd')]The issue?

The assignment expression idx := idx + 1 evaluates to what is being put into idx,

which is the incremented value.

This means that we ignore the start value that idx was set to.

So, if we are off by one, we can fix this in one of two ways.

- We can decrement the initial value of the variable

idx, to compensate for the increment inside the assignment expression:

def gen_indices(start):

idx = start - 1

while True:

yield (idx := idx + 1)However, this is not so elegant because it makes it look like we are not respecting the parameter start in some way...

- Alternatively, we can decrement the value that we are about to yield:

def gen_indices(start):

idx = start

while True:

yield (idx := idx + 1) - 1However, this is not so elegant because it makes it look like we are undoing the increment we just did.

I find both options to be inelegant, which I often take to mean I took the wrong turn somewhere.

It is important to note that writing short code is not the purpose of Python.

Therefore, it may very well be that the initial definition of gen_indices is the one we go with:

def gen_indices(start):

idx = start

while True:

yield idx

idx += 1And yet, I am not convinced this is the best we can do... Once more, feels like we had the right instinct... But the wrong execution! In particular, we were slightly sidetracked by the fact that we had a chance of using a nice new feature of Python.

So, if we had the right instinct but the wrong execution, what would the right execution look like..?

The right tool for the job

Python is a huge language, especially because its standard library is immense, so I often go digging there when I suspect I am trying to implement something absurdly simple.

Sometimes, my gut feeling is flat out wrong (I'm looking at you, sign function),

but I am pleased to say my gut gets this right plenty of times.

In this particular case,

we had the right instinct in replacing the range with an infinite generator that produces the indices...

We just failed to realise this was already in the standard library,

waiting to be imported:

from itertools import countThat's it: itertools.count is the tool for the job:

>>> help(count)## ...

| Equivalent to:

| def count(firstval=0, step=1):

| x = firstval

| while 1:

| yield x

| x += stepNotice how count is remarkably similar to what we had!

That's not a coincidence,

because count is useful in the type of situation where we were using gen_indices.

This also has a silverlining:

seeing that count from the standard library is so similar to our gen_indices shows that our code was pretty good!

Hence, by using the right tool for the job,

our enumerate_ becomes:

from itertools import count

def enumerate_(iterable, start=0):

for idx, elem in zip(count(start), iterable):

yield idx, elemIn case you are worried, it still works:

>>> list(enumerate_("rod"))

[(0, 'r'), (1, 'o'), (2, 'd')]You probably know that there is always something new to learn in Python... My advice? Learn about the tools in the standard library! By using the right tool for the job you write more expressive code, and knowing how to harness the power of the Python Standard Library is a must-have skill for Python programmers.

Yielding from another iterable

Now that we are no longer being sidetracked by the generator for the indices,

we can take a closer look at the for loop that we have implemented.

In particular, we can see that the looping variables match what we are yielding 100%.

So much so, that we really don't need to unpack the two values into idx and elem,

only to then bundling them together.

In fact, we can have a single variable to reduce the amount of work that Python has to do:

>>> from itertools import count

>>> def enumerate_(iterable, start=0):

... for idx_elem in zip(count(start), iterable):

... yield idx_elem

...

>>> list(enumerate_("rod"))

[(0, 'r'), (1, 'o'), (2, 'd')]You may find this a cute little variable name,

but let me actually replace the descriptive name with a bare t:

from itertools import count

def enumerate_(iterable, start=0):

for t in zip(count(start), iterable):

yield tNotice what is happening here:

we get a value from the zip, then we yield it;

then we get another value from zip, then we yield it;

etc...

All our for loop does is yield from the zip object we created:

our enumerate_ takes an iterable,

builds another iterable with the argument,

and then yields from that other iterable.

This pattern is so common that there is a keyword for that!

(Or should I say keyphrase?)

yield from is what we are looking for:

>>> from itertools import count

>>> def enumerate_(it, start=0):

... yield from zip(count(start), it)

...

>>> list(enumerate_("rod"))

[(0, 'r'), (1, 'o'), (2, 'd')]Isn't this cool?

Challenge: <class 'enumerate'>

Before we conclude, I would like you to turn your attention to another detail.

If you look closely, Python says that enumerate is a class:

>>> enumerate

<class 'enumerate'>On the other hand, enumerate_ is a generator function:

>>> enumerate_

<function enumerate_ at 0x00000230C466EF70>Can we make it so that enumerate_ mimics enumerate more closely?

In other words,

can we implement enumerate_ as a class?

What would that even mean?

Can we implement enumerate_ as a class that produces objects that are lazy iterables?

Yeah, we absolutely can, but that would be a topic for a whole other article/talk!

Conclusion

We've gone through half a dozen dummy reimplementations of the built-in enumerate,

which allowed us to take a look at

- idioms for

forloops (using direct iteration,zip,enumerate, etc); - the concept of “iterable”;

- what generators are and how to define one with

yield; - the purpose of

zip; - how to write infinite generators;

- how to fetch values from generators manually with

next; - the module

itertoolsand its classcount; and - how to yield from another generator with

yield from.

On top of all the technical insights you gained, it is also relevant to highlight how we followed our gut, which didn't always get it right the first time. We weren't afraid to experiment, and we played around with things until they made sense. On top of that, we never aimed for the perfect solution; we only ever aimed for repeated improvements!

Become the smartest Python 🐍 developer in the room 🚀

Every Monday, you'll get a Python deep dive that unpacks a topic with analogies, diagrams, and code examples so you can write clearer, faster, and more idiomatic code.

References

- “Zip-up” Pydon't, https://mathspp.com/blog/pydonts/zip-up [last accessed 19-02-2022];

- “Bite-sized refactoring” Pydon't, https://mathspp.com/blog/pydonts/bite-sized-refactoring [last accessed 19-02-2022];

- “Why mastering Python is impossible, and why that's ok” Pydon't, https://mathspp.com/blog/pydonts/why-mastering-python-is-impossible [last accessed 19-02-2022];

- Twitter thread on

enumerate, https://twitter.com/mathsppblog/status/1455444589603557378 [last accessed 19-02-2022];