(If you are new here and have no idea what a Pydon't is, you may want to read the Pydon't Manifesto.)

Introduction

Structural pattern matching is coming to Python, and while it may look

like a plain switch statement like many other languages have,

Python's match statement was not introduced to serve as a simple

switch statement.

PEPs 634, 635, and 636 have plenty of information on what structural pattern matching is bringing to Python, how to use it, the rationale for adding it to Python, etc. In this article I will try to focus on using this new feature to write beautiful code.

At the time of writing, Python 3.10 is still a pre-release, so you have to look in the right place if you want to download Python 3.10 and play with it.

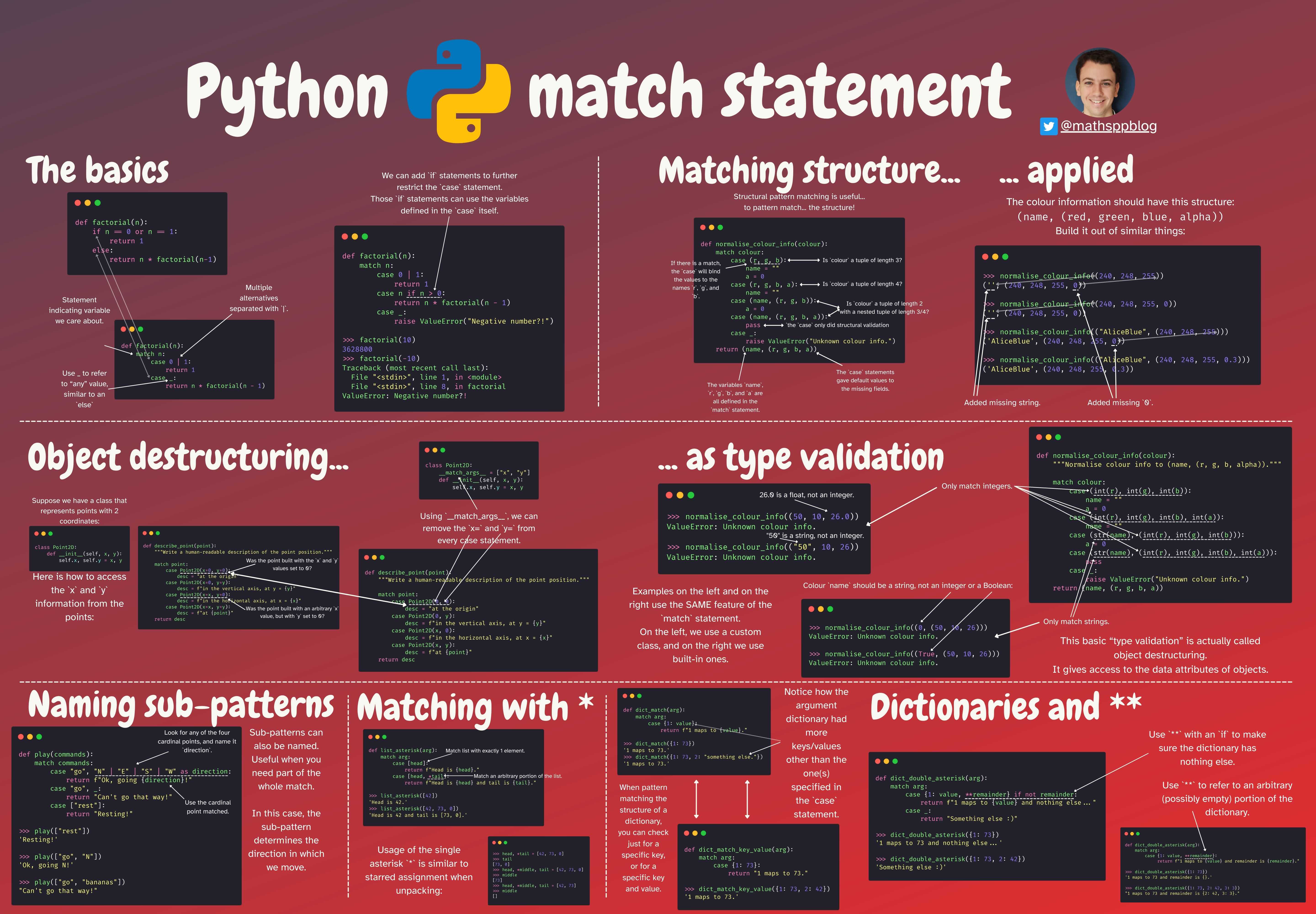

I also summarised the contents of this article in a cheatsheet that you can get for free from here.

Structural pattern matching Python could already do

Structural pattern matching isn't completely new in Python. For a long time now, we have been able to do things like starred assignments:

>>> a, *b, c = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

>>> a

1

>>> b

[2, 3, 4]

>>> c

5And we can also do deep unpacking:

>>> name, (r, g, b) = ("red", (250, 23, 10))

>>> name

'red'

>>> r

250

>>> g

23

>>> b

10I covered these in detail in “Unpacking with starred assignments” and “Deep unpacking”, so go read those Pydon'ts if you are unfamiliar with how to use these features to write Pythonic code.

The match statement will use ideas from both starred assignments

and deep unpacking, so knowing how to use them is going to be helpful.

Your first match statement

For your first match statement, let's implement the factorial function. A factorial function is a textbook example when introducing people to recursion, and you could write it like so:

def factorial(n):

if n == 0 or n == 1:

return 1

else:

return n * factorial(n-1)

factorial(5) # 120Instead of using an if statement, we could use a match:

def factorial(n):

match n:

case 0 | 1:

return 1

case _:

return n * factorial(n - 1)

factorial(5)Notice a couple of things here:

we start our match statement by typing match n, meaning

we will want to do different things depending on what n is.

Then, we have case statements that can be thought of the

different possible scenarios we want to handle.

Each case must be followed by a pattern that we will try

to match n against.

Patterns can also contain alternatives, denoted by the |

in case 0 | 1, which matches if n is either 0 or 1.

The second pattern, case _:, is the go-to way of matching

anything (when you don't care about what you are matching),

so it is acting more or less like the else of

the first definition.

Pattern matching the basic structure

While match statements can be used like plain if statements,

as you have seen above, they really shine when you are dealing

with structured data:

def normalise_colour_info(colour):

"""Normalise colour info to (name, (r, g, b, alpha))."""

match colour:

case (r, g, b):

name = ""

a = 0

case (r, g, b, a):

name = ""

case (name, (r, g, b)):

a = 0

case (name, (r, g, b, a)):

pass

case _:

raise ValueError("Unknown colour info.")

return (name, (r, g, b, a))

## Prints ('', (240, 248, 255, 0))

print(normalise_colour_info((240, 248, 255)))

## Prints ('', (240, 248, 255, 0))

print(normalise_colour_info((240, 248, 255, 0)))

## Prints ('AliceBlue', (240, 248, 255, 0))

print(normalise_colour_info(("AliceBlue", (240, 248, 255))))

## Prints ('AliceBlue', (240, 248, 255, 0.3))

print(normalise_colour_info(("AliceBlue", (240, 248, 255, 0.3))))Notice here that each case contains an expression like the left-hand side

of an unpacking assignment, and when the structure of colour matches

the structure that the case exhibits, then the names get assigned to the

variable names in the case.

This is a great improvement over the equivalent code with if statements:

def normalise_colour_info(colour):

"""Normalise colour info to (name, (r, g, b, alpha))."""

if not isinstance(colour, (list, tuple)):

raise ValueError("Unknown colour info.")

if len(colour) == 3:

r, g, b = colour

name = ""

a = 0

elif len(colour) == 4:

r, g, b, a = colour

name = ""

elif len(colour) != 2:

raise ValueError("Unknown colour info.")

else:

name, values = colour

if not isinstance(values, (list, tuple)) or len(values) not in [3, 4]:

raise ValueError("Unknown colour info.")

elif len(values) == 3:

r, g, b = values

a = 0

else:

r, g, b, a = values

return (name, (r, g, b, a))I tried writing a decent, equivalent piece of code to the one using

structural pattern matching, but this doesn't look that good.

Someone else has suggested, in the comments,

another alternative that also doesn't use match.

That suggestion looks better than mine, but is much more complex

and larger than the alternative with match.

The match version becomes even better when we add type validation to it,

by asking for the specific values to actually match Python's built-in types:

def normalise_colour_info(colour):

"""Normalise colour info to (name, (r, g, b, alpha))."""

match colour:

case (int(r), int(g), int(b)):

name = ""

a = 0

case (int(r), int(g), int(b), int(a)):

name = ""

case (str(name), (int(r), int(g), int(b))):

a = 0

case (str(name), (int(r), int(g), int(b), int(a))):

pass

case _:

raise ValueError("Unknown colour info.")

return (name, (r, g, b, a)))

## Prints ('AliceBlue', (240, 248, 255, 0))

print(normalise_colour_info(("AliceBlue", (240, 248, 255))))

## Raises # ValueError: Unknown colour info.

print(normalise_colour_info2(("Red", (255, 0, "0"))))How do you reproduce all this validation with if statements..?

Matching the structure of objects

Structural pattern matching can also be used to match the

structure of class instances.

Let us recover the Point2D class I have used as an example

in a couple of posts, in particular the

Pydon't about __str__ and __repr__:

class Point2D:

"""A class to represent points in a 2D space."""

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.x = x

self.y = y

def __str__(self):

"""Provide a good-looking representation of the object."""

return f"({self.x}, {self.y})"

def __repr__(self):

"""Provide an unambiguous way of rebuilding this object."""

return f"Point2D({repr(self.x)}, {repr(self.y)})"Imagine we now want to write a little function that takes a Point2D and

writes a little description of where the point lies.

We can use pattern matching to capture the values of the x and y attributes

and, what is more, we can use short if statements to help narrow down the

type of matches we want to succeed!

Take a look at the following:

def describe_point(point):

"""Write a human-readable description of the point position."""

match point:

case Point2D(x=0, y=0):

desc = "at the origin"

case Point2D(x=0, y=y):

desc = f"in the vertical axis, at y = {y}"

case Point2D(x=x, y=0):

desc = f"in the horizontal axis, at x = {x}"

case Point2D(x=x, y=y) if x == y:

desc = f"along the x = y line, with x = y = {x}"

case Point2D(x=x, y=y) if x == -y:

desc = f"along the x = -y line, with x = {x} and y = {y}"

case Point2D(x=x, y=y):

desc = f"at {point}"

return "The point is " + desc

## Prints "The point is at the origin"

print(describe_point(Point2D(0, 0)))

## Prints "The point is in the horizontal axis, at x = 3"

print(describe_point(Point2D(3, 0)))

## Prints "# The point is along the x = -y line, with x = 3 and y = -3"

print(describe_point(Point2D(3, -3)))

## Prints "# The point is at (1, 2)"

print(describe_point(Point2D(1, 2)))__match_args__

Now, I don't know if you noticed, but didn't all the x= and y=

in the code snippet above annoy you?

Every time I wrote a new pattern for a Point2D instance, I had to specify

what argument was x and what was y.

For classes where this order is not arbitrary, we can use __match_args__

to tell Python how we would like match to match the attributes of our object.

Here is a shorter version of the example above, making use of __match_args__

to let Python know the order in which arguments to Point2D should match:

class Point2D:

"""A class to represent points in a 2D space."""

__match_args__ = ["x", "y"]

def __init__(self, x, y):

self.x = x

self.y = y

def describe_point(point):

"""Write a human-readable description of the point position."""

match point:

case Point2D(0, 0):

desc = "at the origin"

case Point2D(0, y):

desc = f"in the vertical axis, at y = {y}"

case Point2D(x, 0):

desc = f"in the horizontal axis, at x = {x}"

case Point2D(x, y):

desc = f"at {point}"

return "The point is " + desc

## Prints "The point is at the origin"

print(describe_point(Point2D(0, 0)))

## Prints "The point is in the horizontal axis, at x = 3"

print(describe_point(Point2D(3, 0)))

## Prints "# The point is at (1, 2)"

print(describe_point(Point2D(1, 2)))Wildcards

Another cool thing you can do when matching things is to use wildcards.

Asterisk *

Much like you can do things like

>>> head, *body, tail = range(10)

>>> print(head, body, tail)

0 [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8] 9where the *body tells Python to put in body whatever does not

go into head or tail, you can use * and ** wildcards.

You can use * with lists and tuples to match the remaining of it:

def rule_substitution(seq):

new_seq = []

while seq:

match seq:

case [x, y, z, *tail] if x == y == z:

new_seq.extend(["3", x])

case [x, y, *tail] if x == y:

new_seq.extend(["2", x])

case [x, *tail]:

new_seq.extend(["1", x])

seq = tail

return new_seq

seq = ["1"]

print(seq[0])

for _ in range(10):

seq = rule_substitution(seq)

print("".join(seq))

"""

Prints:

1

11

21

1211

111221

312211

13112221

1113213211

31131211131221

13211311123113112211

11131221133112132113212221

"""This builds the sequence I showed above, where each number is derived

from the previous one by looking at its digits and describing what you

are looking at.

For example, when you find three equal digits in a row, like "222", you

rewrite that as "32" because you are seeing three twos.

With the match statement this becomes much cleaner.

In the case statements above, the *tail part of the pattern matches the

remainder of the sequence, as we are only using x, y, and z to match

in the beginning of the sequence.

Plain dictionary matching

Similarly, we can use ** to match the remainder of a dictionary.

But first, let us see what is the behaviour when matching dictionaries:

d = {0: "oi", 1: "uno"}

match d:

case {0: "oi"}:

print("yeah.")

## prints yeah.While d has a key 1 with a value "uno", and that is not specified

in the only case statement, there is a match and we enter the statement.

When matching with dictionaries, we only care about matching the structure

that was explicitly mentioned, and any other extra keys that the original

dictionary has are ignored.

This is unlike matching with lists or tuples, where the match has to be

perfect if no wildcard is mentioned.

Double asterisk **

However, if you want to know what the original dictionary had that was

not specified in the match, you can use a ** wildcard:

d = {0: "oi", 1: "uno"}

match d:

case {0: "oi", **remainder}:

print(remainder)

## prints {1: 'uno'}Finally, you can use this to your advantage if you want to match a dictionary that contains only what you specified:

d = {0: "oi", 1: "uno"}

match d:

case {0: "oi", **remainder} if not remainder:

print("Single key in the dictionary")

case {0: "oi"}:

print("Has key 0 and extra stuff.")

## Has key 0 and extra stuff.You can also use variables to match the values of given keys:

d = {0: "oi", 1: "uno"}

match d:

case {0: zero_val, 1: one_val}:

print(f"0 mapped to {zero_val} and 1 to {one_val}")

## 0 mapped to oi and 1 to unoNaming sub-patterns

Sometimes you may want to match against a more structured pattern,

but then give a name to a part of the pattern, or to the whole thing,

so that you have a way to refer back to it.

This may happen especially when your pattern has alternatives,

which you add with |:

def go(direction):

match direction:

case "North" | "East" | "South" | "West":

return "Alright, I'm going!"

case _:

return "I can't go that way..."

print(go("North")) # Alright, I'm going!

print(go("asfasdf")) # I can't go that way...Now, imagine that the logic to handle that “going” somewhere is nested inside something more complex:

def act(command):

match command.split():

case "Cook", "breakfast":

return "I love breakfast."

case "Cook", *wtv:

return "Cooking..."

case "Go", "North" | "East" | "South" | "West":

return "Alright, I'm going!"

case "Go", *wtv:

return "I can't go that way..."

case _:

return "I can't do that..."

print(act("Go North")) # Alright, I'm going!

print(act("Go asdfasdf")) # I can't go that way...

print(act("Cook breakfast")) # I love breakfast.

print(act("Drive")) # I can't do that...And, not only that, we want to know where the user wants to go, in order to include that in the message. We can do this by leaving the options up, but then capturing the result of the match in a variable:

def act(command):

match command.split():

case "Cook", "breakfast":

return "I love breakfast."

case "Cook", *wtv:

return "Cooking..."

case "Go", "North" | "East" | "South" | "West" as direction:

return f"Alright, I'm going {direction}!"

case "Go", *wtv:

return "I can't go that way..."

case _:

return "I can't do that..."

print(act("Go North")) # Alright, I'm going North!

print(act("Go asdfasdf")) # I can't go that way...Traversing recursive structures

Another type of situation in which structural pattern matching is expected to succeed quite well is in handling recursive structures.

I have seen great examples of this use-case in the references I included below, and will now share one of my own.

Imagine you want to transform a mathematical expression into

prefix notation, e.g. "3 * 4" becomes "* 3 4"

and 1 + 2 + 3 becomes + 1 + 2 3 or + + 1 2 3 depending

on whether + associates from the left or from the right.

You can write a little match to deal with this:

import ast

def prefix(tree):

match tree:

case ast.Expression(expr):

return prefix(expr)

case ast.Constant(value=v):

return str(v)

case ast.BinOp(lhs, op, rhs):

match op:

case ast.Add():

sop = "+"

case ast.Sub():

sop = "-"

case ast.Mult():

sop = "*"

case ast.Div():

sop = "/"

case _:

raise NotImplementedError()

return f"{sop} {prefix(lhs)} {prefix(rhs)}"

case _:

raise NotImplementedError()

print(prefix(ast.parse("1 + 2 + 3", mode="eval"))) # + + 1 2 3

print(prefix(ast.parse("2**3 + 6", mode="eval")) # + * 2 3 6

## Prints '- + 1 * 2 3 / 5 7', take a moment to digest this one.

print(prefix(ast.parse("1 + 2*3 - 5/7", mode="eval")))Careful with the hype

Now, here is a word of caution: match isn't the best solution always.

Looking up to the prefix notation example above, perhaps there are better ways to

transform each possible binary operator to its string representation..?

The current solution spends two lines for each different operator,

and if we add support for many more binary operators, that part

of the code will become unbearably long.

In fact, we can (and probably should) do something else about that. For example,

import ast

def op_to_str(op):

ops = {

ast.Add: "+",

ast.Sub: "-",

ast.Mult: "*",

ast.Div: "/",

}

return ops.get(op.__class__, None)

def prefix(tree):

match tree:

case ast.Expression(expr):

return prefix(expr)

case ast.Constant(value=v):

return str(v)

case ast.BinOp(lhs, op, rhs):

sop = op_to_str(op)

if sop is None:

raise NotImplementedError()

return f"{sop} {prefix(lhs)} {prefix(rhs)}"

case _:

raise NotImplementedError()

print(prefix(ast.parse("1 + 2 + 3", mode="eval"))) # + + 1 2 3

print(prefix(ast.parse("2*3 + 6", mode="eval")) # + * 2 3 6

## Prints '- + 1 * 2 3 / 5 7', take a moment to digest this one.

print(prefix(ast.parse("1 + 2*3 - 5/7", mode="eval")))Conclusion

Here's the main takeaway of this article, for you, on a silver platter:

“Structural pattern matching introduces a feature that can simplify and increase the readability of Python code in many cases, but it will not be the go-to solution in every single situation.”

This Pydon't was also summarised in a free cheatsheet:

This Pydon't showed you that:

- structural pattern matching with the

matchstatement greatly extends the power of the already-existing starred assignment and structural assignment features; - structural pattern matching can match literal values and arbitrary patterns

- patterns can include additional conditions with

ifstatements - patterns can include wildcards with

*and** -

matchstatements are very powerful when dealing with the structure of class instances -

__match_args__allows to define a default order for arguments to be matched in when a custom class is used in acase - built-in Python classes can be used in

casestatements to validate types

If you liked this Pydon't be sure to leave a reaction below and share this with your friends and fellow Pythonistas. Also, don't forget to subscribe to the newsletter so you don't miss a single Pydon't!

Become the smartest Python 🐍 developer in the room 🚀

Every Monday, you'll get a Python deep dive that unpacks a topic with analogies, diagrams, and code examples so you can write clearer, faster, and more idiomatic code.

References

- PEP 622 -- Structural Pattern Matching, https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0622/;

- PEP 634 -- Structural Pattern Matching: Specification, https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0634/;

- PEP 635 -- Structural Pattern Matching: Motivation and Rationale, https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0635/;

- PEP 636 -- Structural Pattern Matching: Tutorial, https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0636/;

- Dynamic Pattern Matching with Python, https://gvanrossum.github.io/docs/PyPatternMatching.pdf;

- Python 3.10 Pattern Matching in Action, YouTube video by “Big Python”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SYTVSeTgL3s.