(If you are new here and have no idea what a Pydon't is, you may want to read the Pydon't Manifesto.)

Introduction

List comprehensions are, hands down, one of my favourite Python features.

It's not THE favourite feature, but that's because Python has a lot of things I really like! List comprehensions being one of those.

This article (the first in a short series) will cover the basics of list comprehensions.

This Pydon't will teach you the following:

- the anatomy of a list comprehension (what parts compose a list comprehension);

- how to create list comprehensions;

- the parallel that exists between some

forloops and list comprehensions; - how to understand list comprehensions if you have a strong mathematical background;

- the four main advantages of list comprehensions;

- the main use case for list comprehensions;

- what are good use cases for list comprehensions; and

- what are bad use cases for list comprehensions.

I also summarised the contents of this article in a cheatsheet that you can get for free from here.

You can get all the Pydon'ts as a free ebook with over +400 pages and hundreds of tips. Download the ebook “Pydon'ts – write elegant Python code” here.

What is a list comprehension?

A list comprehension is a Python expression that builds a list. That's it, really.

In other words, list comprehensions are great because they provide a very convenient syntax to create lists.

If you come from a functional language, have a strong mathematical background, or if you are just very comfortable with maths notation, you may have an easier time learning about list comprehensions from first principles.

For people who already know Python, list comprehensions are best understood when compared to a for loop, so let me show you that.

A loop that builds a list

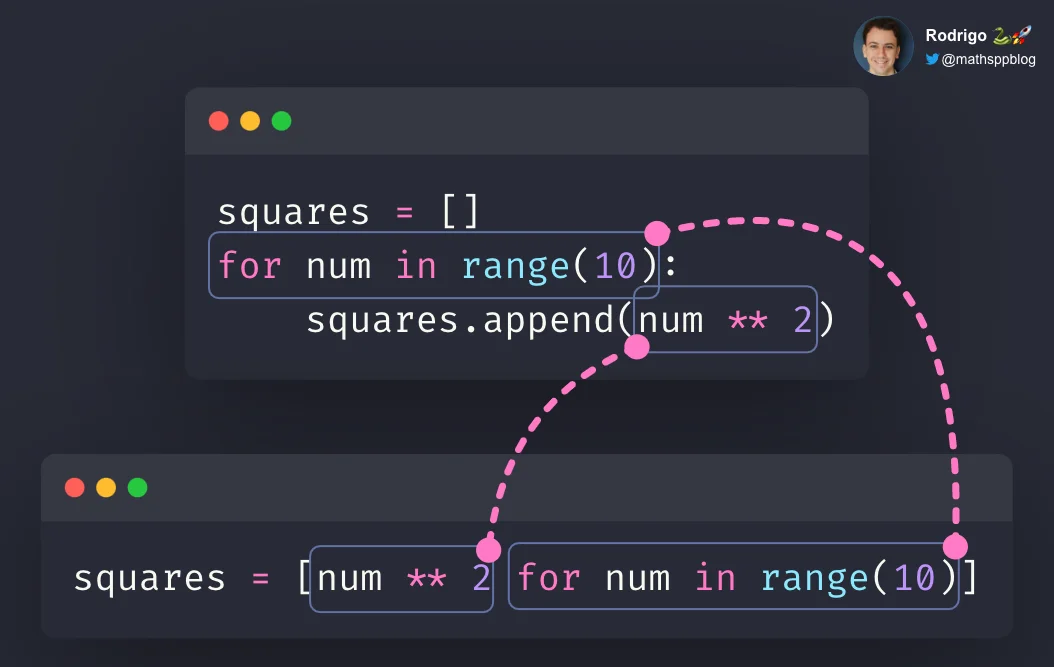

Consider the loop below.

It builds a list called squares which contains the first square numbers:

squares = []

for num in range(10):

squares.append(num ** 2)This loop exhibits a very common pattern:

given an iterable (in this case, range(10)), do something with each of its elements, one by one, and append the result to a new list (in this case, squares).

The key idea behind list comprehensions is that many lists can be built out of other, simpler iterables (lists, tuples, strings, range, ...) by transforming the data that we get from those iterables.

In those cases, we want to focus on the data transformation that we are doing.

So, in the case of the loop above, the equivalent list comprehension would look like like this:

squares = [num ** 2 for num in range(10)]What we can see, by comparing the two, is that the list comprehension extracts the most important bits out of the loop and then drops the fluff:

In short, the version with the list comprehension drops:

- the initialisation of the list (

squares = []); and - the call to

append(squares.append(...)).

I want you to understand that the list comprehension is exactly like the loop, except things are reordered to move what's inside append to the beginning.

The animation below shows how this process works in the general case:

Exercises: practice rewriting for loops as list comprehensions

Practice makes perfect, so I have a couple of loops for you to practice on. Go ahead and convert the loops below into list comprehensions.

We'll start off with an easy one. Can you redo the example I showed earlier?

- Computing the first square numbers:

squares = []

for n in range(10):

squares.append(num ** 2)- Uppercasing a series of words:

fruits = "banana pear peach strawberry tomato".split()

upper_words = []

for fruit in fruits:

upper_words.append(fruit.upper())- Find the length of each word in a sentence:

words = "the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog".split()

lengths = []

for word in words:

lengths.append(len(word))If you want +250 exercises on list comprehensions and all related concepts, check out my book “Comprehending Comprehensions”.

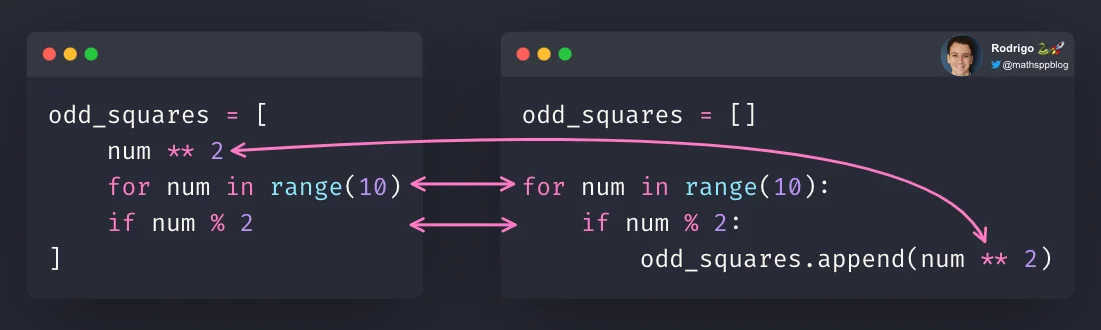

Filtering data in a list comprehension

The list comprehensions we have covered so far let you build a new list by transforming data from a source iterable. However, list comprehensions also allow you to filter data so that the new list only transforms some of the data that comes from the source iterable.

For example, let's modify the previous loop that built a list of squares. This time, we'll square only numbers that are divisible by 3 or 5. Kind of like a twist on the “Fizz-Buzz” problem.

fizz_buzz_squares = []

for num in range(10):

if (num % 3 == 0) or (num % 5 == 0):

fizz_buzz_squares.append(num ** 2)(For educational purposes, we're ignoring the fact that we could've just used range(1, 10, 2).)

Again, this is a common pattern that can easily be converted into a list comprehension. Because the data filter is optional (we built a list comprehension before without it), it goes in the end of the list comprehension:

fizz_buzz_squares = [

num ** 2 # Data transformation

for num in range(10) # Data source

if (num % 3 == 0) or (num % 5 == 0) # Data filter

]Notice the order of the three components of the list comprehension:

- data transformation (

num ** 2); - sourcing the data (

for num in range(10)); and - filtering the data (

num % 2).

A list comprehension may be written across multiple lines to improve its readability, as you saw above. If I didn't split the list comprehension across multiple lines, it would end up being too long, harming its readability.

When splitting a list comprehension across multiple lines, I am a personal fan of having the three components on separate lines. (It may or may not be related to the fact that code formatting tools like black do the same thing!) I'll say it again to make sure you get this: it is OK for list comprehensions to span across multiple lines. They don't have to be written in a single line.

In particular, if you are writing your first list comprehensions, the multi-line representation makes the list comprehension look more like the explicit for loop with a conditional expression.

This should make the list comprehension easier to read.

The diagram below shows this relationship:

To recap, here’s how you transform a for loop with an if statement into a list comprehension:

More exercises

Go ahead and convert the loops below into list comprehensions to practice.

- Squaring:

fizz_buzz_squares = []

for n in range(10):

if (num % 3 == 0) or (num % 5 == 0):

fizz_buzz_squares.append(n ** 2)- Upper casing words:

fruits = "Banana pear PEACH strawberry tomato".split()

upper_cased = []

for word in words:

if word.islower():

upper_cased.append(word.upper())- Finding length of words:

words = "the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog".split()

lengths = []

for word in words:

if "o" in word:

lengths.append(len(word))If you want +250 exercises on list comprehensions and related concepts, check out my book “Comprehending Comprehensions”.

List comprehensions from first principles

In this section, I present list comprehensions as a construct that has merit on its own rather than something derived from a common for loop pattern.

To present list comprehensions “from first principles”, I will draw comparisons from standard mathematical notation.

I find that this relationship between list comprehensions and mathematics is very englightening, but I can also sympathise with the fact that not everyone cares.

If that's the case, you can skip ahead to read about the full anatomy of a list comprehension.

The idea of a list comprehension is to provide a syntactical construct that lets you build lists, much like literal list notation. However, when writing out a list literal you need to write down every single element you want in your list:

squares = [0, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, 64, 81]In the case above, you had to write down ten elements explicitly.

A bit annoying, but manageable.

What if, instead of ten, you wanted your list squares to contain 500 square numbers?

In that case, it would be infeasible to write every square by hand.

Instead, we use a list comprehension to describe what elements we want in our list squares.

A list comprehension, akin to the mathematical set notation, is a way to define a list by comprehensively describing which elements you want in the list without having to write down all of them.

For example, we can use mathematical notation to define something similar to the list squares above:

\[ \{n^2| ~ n = {0, ~ \dots, ~ 9}\}\]

The \(n^2\) is the description of what we want: the squares. The \(n = {0, ~ \dots, ~ 9}\) complements the description by saying where we get the values of \(n\) from. The two, together, give us enough information to determine what are the contents of the object we're building.

I can change the second part so that now I have 500 squares:

\[ \{n^2| ~ n = 0, ~ \dots, ~ 499\}\]

I can also change the first part so that now I have 500 cubes:

\[ \{n^3| ~ n = 0, ~ \dots, ~ 499\}\]

This notation provides a shortcut to define arbitrarily big sets in mathematics.

In Python, we can do a similar thing.

The description of what we want can be any Python expression whatsoever (for example, a function call, a method call, or a mathematical computation).

Then, the Python equivalent to the mathematical bit \(n = 0, ~ \dots, ~ 499\) is a for loop specifying an iterable from where we get our values.

squares = [n ** 2 for n in range(10)]

# ^^^^^^ ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ This specifies where we get the data from.

# ^^^^^^ This describes what we want (squares).In addition to specifying where the data comes from, we can specify further restrictions – or filters – on the data we use. For example, we can expand our example to compute more squares, but only if \(n\) is divisible by 3 or 5:

\[ \{n^2| ~ n = {0, ~ \dots, ~ 999}, 3 | n \vee 5 | n \}\]

(The \(3 | n\) in mathematics is similar to a n % 3 == 0 in Python.)

Here's how that looks as a list comprehension, where we use an if statement to do the data filtering:

squares = [n ** 2 for n in range(1000) if (n % 3 == 0) or (n % 5 == 0)]For readability, you may prefer to split the components of the list comprehension over multiple lines:

squares = [

n ** 2

for n in range(100)

if (n % 3 == 0) or (n % 5 == 0)

]This is useful if your list comprehension becomes long. In fact, this is so useful that many linters will do it for you.

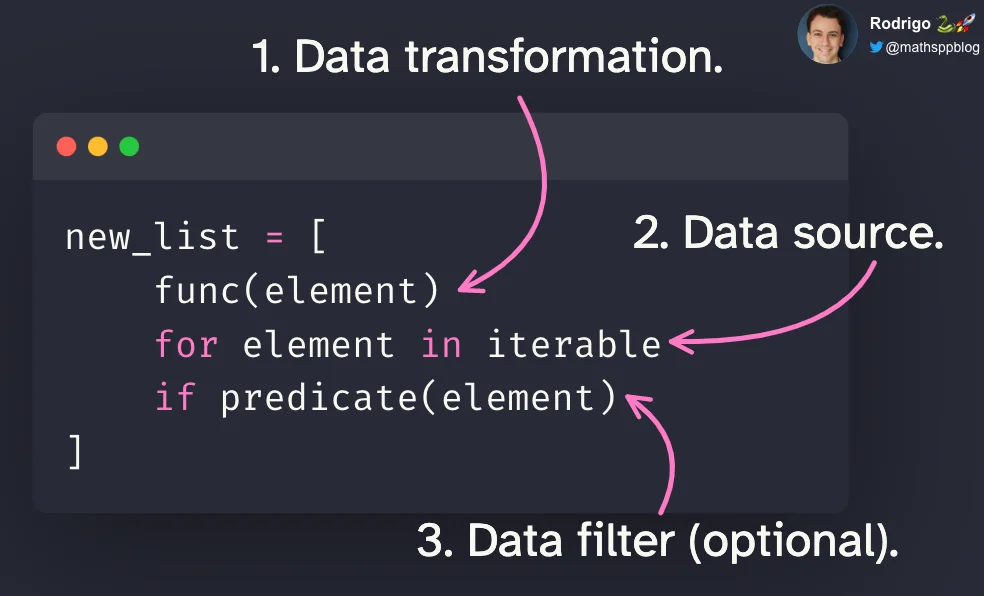

Full anatomy of a list comprehension

As you've seen, the anatomy of a list comprehension is dictated by three components enclosed in square brackets []:

- a data transformation;

- a data source; and

- a data filter (which is optional).

This is summarised in the diagram below:

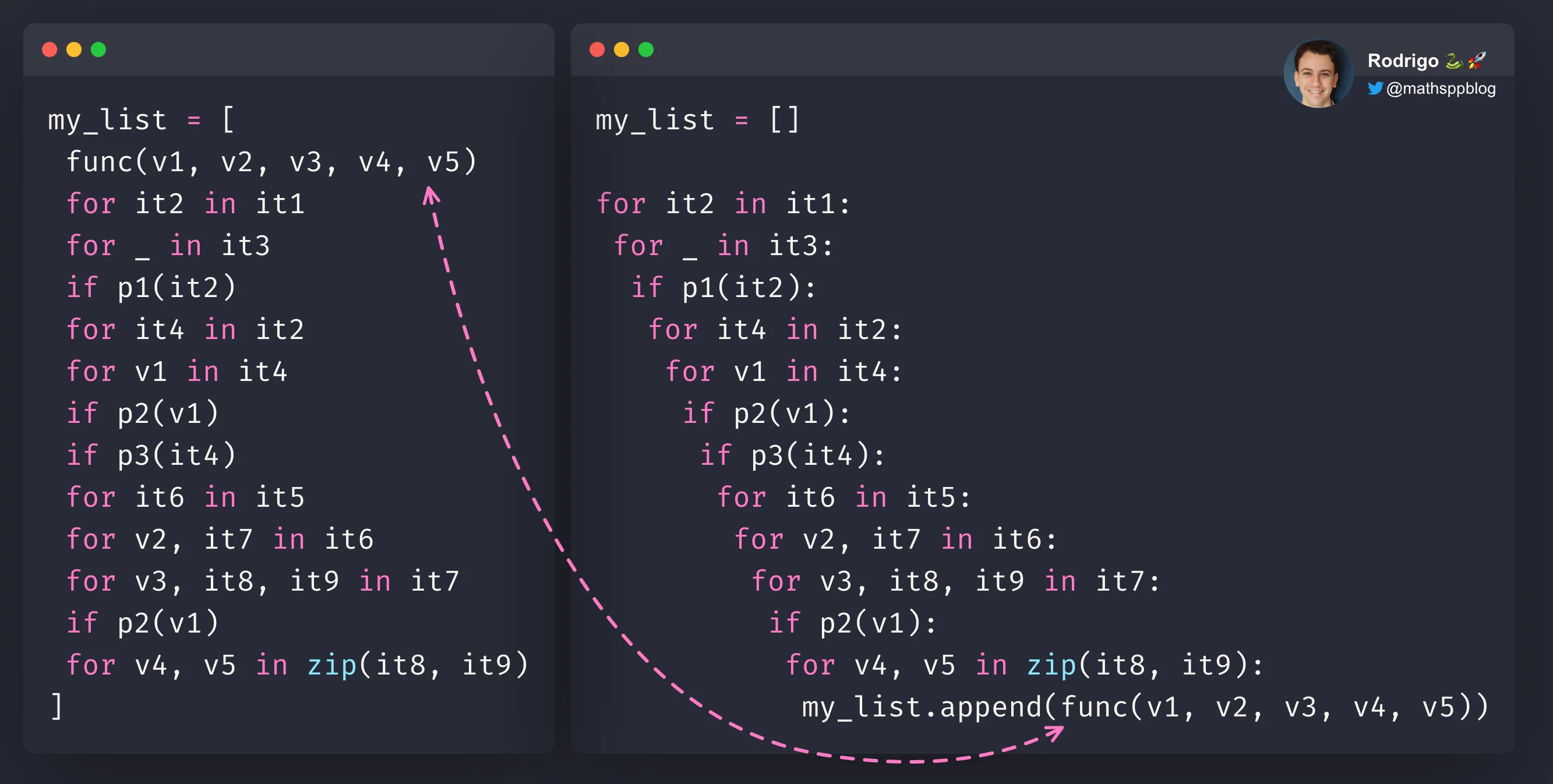

Note that Python does not impose any restrictions on the number of data sources or data filters in a list comprehension, much like you can nest for loops and if statements arbitrarily.

For example, the nested structure below, which contains 12 statements, could be converted into a list comprehension:

my_list = []

for it2 in it1:

for _ in it3:

if p1(it2):

for it4 in it2:

for v1 in it4:

if p2(v1):

if p3(it4):

for it6 in it5:

for v2, it7 in it6:

for v3, it8, it9 in it7:

if p2(v1):

for v4, v5 in zip(it8, it9):

my_list.append(func(v1, v2, v3, v4, v5))In fact, converting the nested structure above into a list comprehension is as difficult as it is to convert a structure with a single loop and a single condition. That's because the mechanics of the transformation are always the same:

- what's inside the call to

appendmoves to the beginning of the list comprehension; and - everything else stays exactly in the same place.

Give it a go yourself. Convert the code above into a list comprehension. You should arrive at this list comprehension:

my_list = [

func(v1, v2, v3, v4, v5)

for it2 in it1

for _ in it3

if p1(it2)

for it4 in it2

for v1 in it4

if p2(v1)

if p3(it4)

for it6 in it5

for v2, it7 in it6

for v3, it8, it9 in it7

if p2(v1)

for v4, v5 in zip(it8, it9)

]Putting both side-by-side highlights the fact that the ordering of the nested statements was preserved:

However, bear in mind that just because it is possible, it doesn't mean you should do it.

List comprehensions should be kept simple and with a relatively small number of data sources and data filters.

For most people, that's just one data source and one data filter (one for and one if) or two data sources and no data filters (two for and zero if).

Advantages of list comprehensions

The main advantages of using list comprehensions over the equivalent nested structures are

- speed;

- conciseness;

- purity; and

- readability.

Let’s briefly explore all the advantages listed above but keep in mind that the main advantage of a list comprehension is its readability.

Speed

List comprehensions are faster than the equivalent loops when we're not dealing with trivial cases because of the internals of CPython. When we have a loop, Python needs to keep going back and forth between C and Python itself to do the looping and computing the elements to append to the new list. List comprehensions are implemented in such a way that we don't need to do this, and because there's less back-and-forth, list comprehensions are slightly faster than the equivalent loop structures.

Conciseness

The animations above have shown that, quite literally, you have to delete code from a loop to turn it into a list comprehension. Thus, a list comprehension is objectively shorter than the equivalent loop.

Note that there is no requirement that list comprehensions fit into one line. This goes against the beliefs of some, who will proudly show their lengthy list comprehension one-liners. If you find such a person, it becomes your job to teach them that list comprehensions can be made to span across multiple lines and that that often improves its readability at no cost.

Purity

“Purity” here is meant in the functional programming sense, or in the mathematical sense.

When a for loop runs, it has a side-effect:

it will create (or modify) the auxiliary variable that is used to loop.

In the example below, we are able to access the variable num, even after the loop is done:

squares = []

for num in range(10):

squares.append(num ** 2)

print(num) # 9, the last value of the loop.This is not the case in a list comprehension, as the variable(s) used in the loop(s) inside a list comprehension are not available outside of the list comprehension.

The example below shows that trying to access num outside of the list comprehension leads to a NameError, because the variable num isn't defined:

squares = [num ** 2 for num in range(10)]

print(num) # NameError, the variable `num` doesn't exist.Because the construct of a list comprehension does not have side effects by nature, there is a convention that you shouldn't use code that creates side effects inside a list comprehension. List comprehensions should be used solely for the purpose of creating new lists by transforming data from other iterables.

Readability

Although readability is a subjective matter, there is something objective to be said about the readability of list comprehensions. List comprehensions, by definition, show the data transformation that they employ at the very beginning. This makes it easier for people reading your code to understand what's going into the list you are creating.

This is especially important if we consider that code is usually read in context. Your list comprehensions/loop will be inside a function, or a method, or in the middle of a script with more context.

For example, consider this incomplete piece of code:

with open("my_file.txt", "r") as my_file:

lines = [...The context manager (the line that goes with open(...) and opens the file) gives you information that is very relevant for the variable lines, which is going to be a list.

When you read the context manager and when you see that there is a variable called lines, you can guess with certainty that the code will iterate over the lines of my_file.

The surrounding code already tells you what the data source is.

What you don't know is what will happen to each line!

Remember, in a list comprehension, the data transformation is the first thing you read:

with open("my_file.txt", "r") as my_file:

lines = [line.strip() ...After you've read that part of the code, you can pretty much guess what comes next, which is for line in my_file.

As we've seen, list comprehensions reorder things so that the most important bit comes first. That's it. This, together with the fact that list comprehensions have less code than the equivalent loop, is the reason that many people feel that list comprehensions are readable.

Examples in code

List comprehensions are not a drop-in replacement for every single loop. List comprehensions are useful when you are building a list out of an existing iterable.

I have a few examples below that show good and bad list comprehension use cases from real-world code. If you want more examples and +250 exercises, check my book “Comprehending Comprehensions”!

Good use cases

Simple list comprehension

# Lib/email/quoprimime.py in Python 3.11

['=%02X' % c for c in range(256)]This list comprehension was taken from the standard library and it is as good as they get. This is a textbook example of a good list comprehension:

- it is short;

- it's applying some string formatting to a bunch of values; and

- we're getting the values directly from a simple iterable,

range(256).

You may or may not need a second to process the string formatting '=%02X' % c, which uses ancient formatting syntax, but you'll need that second regardless of whether we have a list comprehension or a loop.

Might as well just see that upfront, so you can spend your brain power on what really matters (understanding the formatting).

Flattening a list of lists

It is perfectly acceptable to use list comprehensions with two loops, and a great example of such a list comprehension is this:

# Lib/asyncio/base_events.py in Python 3.11

[exc for sub in exceptions for exc in sub]What this list comprehension does is flatten a list of lists.

That's it.

This is a very common pattern!

Just bear in mind that there is another tool in the standard library that does a similar thing and that may be better, depending on your use case:

itertools.chain

.

Filtering one iterable with another one

# Lib/_pydecimal.py in Python 3.11

[sig for sig, v in self.flags.items() if v]This list comprehension shows another pattern that is quite common, in which we are filtering elements of one iterable based on the values of a second iterable.

In this case, we are actually getting keys and values from a dictionary, but this is also commonly done by putting together two iterables with the built-in zip.

Initialising data

This example comes from the [Textual][textual] code base:

# src/textual/_compository.py in Textual 0.36.0

[[0, width] for _ in range(height)]This is a personal favourite of mine and shows how to initialise a list with data. In the snippet above, we create a list that contains the same value repeatedly. I also use a similar pattern to create random data. For example, here is how I would create a random RGB colour:

from random import randint

colour = [randint(0, 255) for _ in range(3)]The key here is the _ inside the loop, which is an idiom that shows we don't care about the value of the current iteration, because we are doing the same thing over and over again.

A simple loop and a simple filter

This one has a bit more context, and it came from an interaction I had on Twitter. While scrolling through Twitter, I found someone writing a little Python script to interact with Amazon Web Services to get IP prefixes for different services. (Whatever that means.)

At some point, they had a simple for loop that was iterating through a bunch of prefixes and storing them in a list, provided that that prefix had to do with a specific Amazon service.

This person is a self-proclaimed Python beginner, and so I thought this was a good opportunity to show how list comprehensions can be useful.

The relevant excerpt of the original code is as follows:

def get_service_prefixes(amazon_service):

aws_prefixes = get_aws_prefixes()

count = 0

service_prefixes = []

for prefix in aws_prefixes["prefixes"]:

if amazon_service in prefix["service"]:

count += 1

service_prefixes.append(prefix["ip_prefix"])

# ...Looking at the code above, we can see that the list service_prefixes is being created and then appended to in the for loop; also, that's the only purpose of that for loop.

This is the generic pattern that indicates a list comprehension might be useful!

Therefore, we can replace the loop with a list comprehension.

The variable count is superfluous because it keeps track of the length of the resulting list, something we can find out easily with the function len.

This is what I proposed:

def get_service_prefixes(amazon_service):

service_prefixes = [

prefix for prefix in get_aws_prefixes()

if amazon_service in prefix["service"]

]

count = len(service_prefixes)

# ...Now, if you were paying attention, you'll notice that I broke my own personal preference in the code above! The list comprehension above was split across two different lines instead of three. That's because my personal preferences and my knowledge evolved with time!

Bad use cases

Let me also show you some examples of bad list comprehensions because list comprehensions aren't something that can replace all of your loops.

Initialising another list

This is something I see beginners do surprisingly often, so I thought I'd get this out of the way right now:

squares = []

[squares.append(num ** 2) for num in range(10)]What's happening above?

We're creating an empty list squares and we're appending to it from inside another list...

Which is totally not the point of list comprehensions!

The issue here is that our list comprehension has side effects (it changes the contents of another list), and list comprehensions are not supposed to have side effects.

Another indication that this list comprehension is flawed – and this is an indicator that you can use yourself – is that the final result of the code does not depend on whether or not we assigned the list comprehension to another variable. In fact, the snippet of code above has a list comprehension that is not assigned to a variable, which means we are creating a list (that's what the list comprehension does), and we're wasting it.

If we were to assign the list comprehension above, this is what the result would look like:

squares = []

some_list = [squares.append(num ** 2) for num in range(10)]

print(some_list) # [None, None, None, None, None, None, None, None, None, None]The reason we get a bunch of None values inside some_list is because that's the return value of the method append.

Side effects

The case above was a very specific version of the bad example I'm showing, which is when the list comprehension has side effects.

In the example below, that's a call to the print function:

[print(value) for value in iterable]Again, how could you know that this is a bad list comprehension?

Because it does things even if you don't assign it to a variable!

This is exactly what a good ol' for loop is for:

for value in iterable:

print(value)List comprehensions can't replace every single for loop!

They're just meant as a tool to build lists.

Replacing built-ins

Another bad use case for list comprehensions is when we're trying to replace some built-in. A common one is this:

lst = [value for value in iterable]This looks like a perfect list comprehension: short and simple! However, the code above is equivalent to

lst = list(iterable)Another built-in you may end up reinventing is reversed.

There is also a lot to be said about the built-ins map and filter, but I will leave that for a follow-up article on the more advanced bits of list comprehensions.

Conclusion

Here's the main takeaway of this Pydon't, for you, on a silver platter:

List comprehensions are a powerful Python feature that lets you build lists in a short and readable way.

This Pydon't showed you that:

- a list comprehension has 4 parts, one of which is optional;

- list comprehensions can transform data drawn from another iterable;

- list comprehensions can filter the data they transform;

- each list comprehension is equivalent to a

forloop that successively calls.appendon a list that is initialised empty; - list comprehensions can nest arbitrarily many

forloops; - list comprehensions can nest arbitrarily many

ifstatements; - list comprehensions are typically faster, shorter, purer, and more readable than their loop counterparts; and

- simple loops whose only job is to append to a

listcan often be replaced with list comprehensions.

This Pydon't was also summarised in a free cheatsheet, and this is just a small part of what I cover in my book “Comprehending Comprehensions”, which covers advanced list comprehensions, set and dictionary comprehensions, generator expressions, and has over 250 exercises with solutions.

If you liked this Pydon't be sure to leave a reaction below and share this with your friends and fellow Pythonistas. Also, subscribe to the newsletter so you don't miss a single Pydon't!

Become the smartest Python 🐍 developer in the room 🚀

Every Monday, you'll get a Python deep dive that unpacks a topic with analogies, diagrams, and code examples so you can write clearer, faster, and more idiomatic code.

References

- Python 3 Docs, The Python Tutorial, Data Structures, More on Lists, List Comprehensions https://docs.python.org/3/tutorial/datastructures.html#list-comprehensions [last accessed on 24-09-2021];

- Python 3 Docs, The Python Standard Library, Built-in Functions,

filter, https://docs.python.org/3/library/functions.html#filter [last accessed 22-09-2021]; - Python 3 Docs, The Python Standard Library, Built-in Functions,

map, https://docs.python.org/3/library/functions.html#map [last accessed 22-09-2021];